Category: "Atmospheric optics"

Hole in Cloud

February 20th, 2022A region of thin, high cloud becomes ice, making a hole. That is what happened in the picture below.

See the blue hole over the mountain? It may not be circular, but it clearly is a gap where once had been cloud.

If you look at that cloud, you might not realize that it consists nearly entirely of droplets. How do I know that?

The (colored) corona around the sun at the bottom right is a diffraction effect that occurs in thin regions containing nearly uniform-sized droplets. The angular position of the colored rings is solely dependent on the ratio of wavelength to droplet size. So, by noting the color and the position of the ring, one can deduce the droplet size in that region of cloud. Right now, we don't care so much about the droplet size as the mere fact that they must be droplets.

However, the droplets are almost certainly all well below the freezing temperature (perhaps below -20 C), so if a droplet happens to freeze, the resulting crystal will grow rapidly. Growing rapidly, it will both dry out the neighboring air, which causes the surrounding drops to evaporate, and the crystal falls. It falls below the cloud, into drier air, and then it too evaporates (actually, we use the term 'sublimate' for solids, but the process is the same).

If you look near the top of the blue hole, you can see a thin wisp of cloud. That wisp consists of falling ice.

So, that explains why there is a hole, but we have to wonder--why did it happen there?

Well, it must have gotten just a little too cold there, perhaps below -30 C. The cloud layer was probably rising as it moved from right-side to left-side (west-to-east), and a wave was produced where the air went over the mountain ridge that you see. The extra rise in that location brought the droplets into higher, and colder, air where they quickly froze. The wave is invisible, but its effect is not.

--JN

Bright Tangent Arc After Sundown

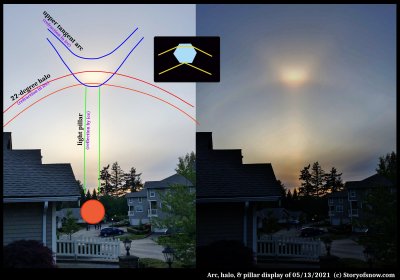

February 20th, 2022Walking the dog in the evening last May, I saw this bright spot in the sky. The sun had just set and quite a few folks had also noticed it.

I had never seen an optical display after sundown, yet could never think of a reason for this. Indeed, there is no physical reason that some ice-crystal reflection and refraction effects should not be visible after sundown. So, I had simply decided my lack of seeing them was simply due to not having the sun as a good reference point to locate the relatively subtle displays.

This case was not subtle. Indeed, as you can see by the people in the picture, even the "ice-display" novices had noticed.

I will keep this brief, but here is a very crude description of what is happening. The image at the right half is with the contrast cranked up high to help make it clearer.

--JN

Odd Radius Haloes and Pyramidal Crystal Faces

February 19th, 2022Out walking one day last spring, I sensed a subdued illumination--like a thin veil of cloud had drifted in front of the sun. I looked up, and indeed found that there was. Blocking out the sun with my hand, I surveyed the thin veil and saw a strange sight: instead of the usual 22-degree halo around the sun, I saw what looked like two closely spaced haloes near the usual 22-degree spot. I took a picture:

Below, I mark the positions of the observed haloes in green and in black the position that the common 22-degree halo should be.

A rare heliac arc? (plus six others)

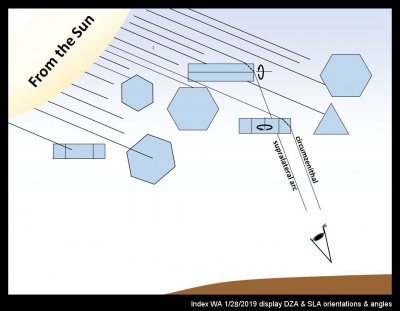

February 5th, 2019The day starts sunny and bright, but later you note a slight muting of the surrounding landscape. It is still bright enough, but you feel less heat bearing down. Apparently, a thin veil of high clouds has slowly and silently appeared above.

When this happens, please take a few seconds to look up and see what these clouds are up to. Do they have their crystals lined up for one or more arcs, or are they oriented randomly, giving a halo with perhaps a sun dog or two? To the trained eye, the chances are high that such a veil will give rewards, even when no crystals are present. But the crystals give so much more, particularly when they line up in various ways.

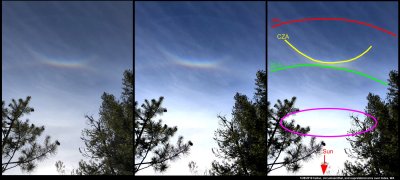

Wandering, somewhat exhausted, on the hillside above Index, WA last Monday, I got this very sense of a muted landscape. So, I found a break in the trees, looked up, and instantly felt recharged. A colorful circumzenithal arc had appeared, which by itself is always a treat. But I was also awed by several other arcs and a very diffuse 22-degree halo. Excitedly, I took photos and scrambled around trees and rock for a more complete view.

(As with all images here, click on the image to see a larger view.)

Due to the complex way the eye and brain discerns light and patterns versus the much simpler way of a camera, the patterns are much more distinct when viewed direct by eye. But the above composition has my attempt to compensate the original photo at left, with some contrast enhancement in the middle version, and markings on the right version.

The band of color at the intersection of CZA and SLA is from the oriented prism crystals of the circumzenithal arc (CZA). Their formation is relatively common I think, though a group of observers in Germany apparently finds their occurrence there to be only about 13 times per year (https://www.atoptics.co.uk/halo/whyinfr.htm). What is most remarkable to me is not their colors, but the fact that formation of distinct colors requires that the crystals stay extremely level as they fall (deviations of only a few degrees would wash out the colors). My sketch below shows roughly what is going on here:

(Hold on for a moment, and I'll get to the rare heliac arc below.)

A Fogbow

October 25th, 2017A fogbow, or cloudbow (fog is a type of cloud), is a special type of rainbow. It is just white, and so not as often photographed as the full-spectrum rainbow, but it can be exciting to see nevertheless.

The reason the fogbow is white is because the water droplets in fog are much smaller than raindrops. Fog droplets may vary in diameter roughly between 1 and 20 millionths of a meter (i.e., 1-20 microns), whereas raindrops are typically 1-3 thousandths of a meter, or about 500 times larger. The wavelength of visible light is only about a half a micron, so the light rays inside a fog droplet are still fairly well defined, but there is simply not enough room to separate out the colors, to state things simply.

Upon approaching a fog in the morning, look towards, but above your shadow. About 50-60 degrees from the shadow of your head is where the fogbow will sit, just as it would for a rainbow. Evenings will work too. But midday, the angles 50-60 degrees above your shadow will have you looking at the ground, so you probably won't see a fogbow there. (If you are in an outdoor shower, you might see a rainbow though.)

The above photograph shows the fogbow I saw yesterday morning, about 8:30 am, biking into a nearby park.

-- JN

It’s not a rainbow (it’s better)

August 12th, 2014In summer, the sun reaches higher elevations, bringing the possibility of new atmospheric displays. I saw this one in mid-June.

The top, upward arc is the more familiar and common 22-degree halo. But pay attention to the one on the bottom. Its colors look like a rainbow, but it has nothing to do with water drops of any sort.

It is the circumhorizontal arc, and it is as rare as it is beautiful. The colors are, in fact, more pure than those of the rainbow, and its origin is far more remarkable. It is remarkable because of the surprising set of conditions that must hold for it to exist. First of all, the particular region of cloud (at a certain angle to our eye) must consist mostly of ice crystals. Second, the crystals there must be nearly perfect tabular prisms. And third, these crystals must be in sufficiently non-turbulent air and of such a size that they fall in a nearly exact horizontal position:

Halo in the sky? Uh, I don't see no halo...

April 20th, 2014After a few days of fine bright spring weather, the barometer falls and a south wind begins to blow. High clouds, fragile and feathery, rise out of the west, the sky gradually becomes milky white, made opalescent by veils of cirro-stratus. The sun seems to shine through ground glass, its outline no longer sharp, but merging into its surroundings. There is a peculiar, uncertain light over the landscape; I 'feel' that there must be a halo round the sun!

And as a rule, I am right.

The quote, from Minneart* describes a common ice-related atmospheric apparition. It appears in skies all over the world far more often than the rainbow, yet few notice it. As a graduate student, I read about halos and often looked for one, but didn't notice it myself until someone else pointed it out. As a post-doc in Boulder, I was out walking with Charles Knight, and I mentioned my lack of success. He glanced up near the sun, pointed, and said “why there's one right now”.

What I had missed in my readings had been the fact that most halos are rather indistinct and often incomplete circles. Indeed, now when I point out the most common one (the 22-degree halo) to someone nearby, they often don't see it. But occasionally, it is sharp enough (and colored) to the extent that anyone will see it if they bother to look up and glance toward the sun. And often it occurs with other ice-crystal apparitions that are even more obvious.

Last fall, while perched high on a rock face, belaying my partner up**, I saw such a vivid display.

The bright spot is called a “sun dog”, “mock sun”, or “parhelia”. They, one on either side of the sun, usually appear together with the 22 degree halo. Indeed, the sun dogs very nearly mark the spots where that halo intersects another arc called the parahelic circle. Their cause: horizontally oriented, tabular ice crystals.

Reflections off Falling Crystals

December 26th, 2009On my morning icespotting trip the other day (12/23), I caught a glimpse of an unusual sight - a sun pillar. I thought I saw one once last winter, but this one was unmistakable. It seemed more striking even than the one in Robert Greenler's book "Rainbows, Haloes, and Glories", a classic book on atmospheric displays. A line of light above the sun forms when sunlight reflects off the bottoms of falling crystals that fall a certain way - nearly horizontal. A pillar can form from either columnar crystals, oriented like a log floating on water, or tabular crystals, oriented like a frisbee in flight. For the reflection to reach our eyes, only the crystals that appear above the sun can reflect sunlight to our eye. So we see the reflections coming from the region directly above the sun, as in the picture. The same effect can occur below the sun, when the sunlight reflects of the tops of the crystals. I took this picture on the sunset setting of my camera, which boosts the reds, but the view to my eye was, if anything, more stunning.

-JN