Category: "Announcements"

Seeing Things in the Frost

January 15th, 2012In looking at the Cloud Appreciation Society's website recently, I started wondering; if they can have so much fun finding clouds that resemble various objects, why can't we do that for frost patterns?

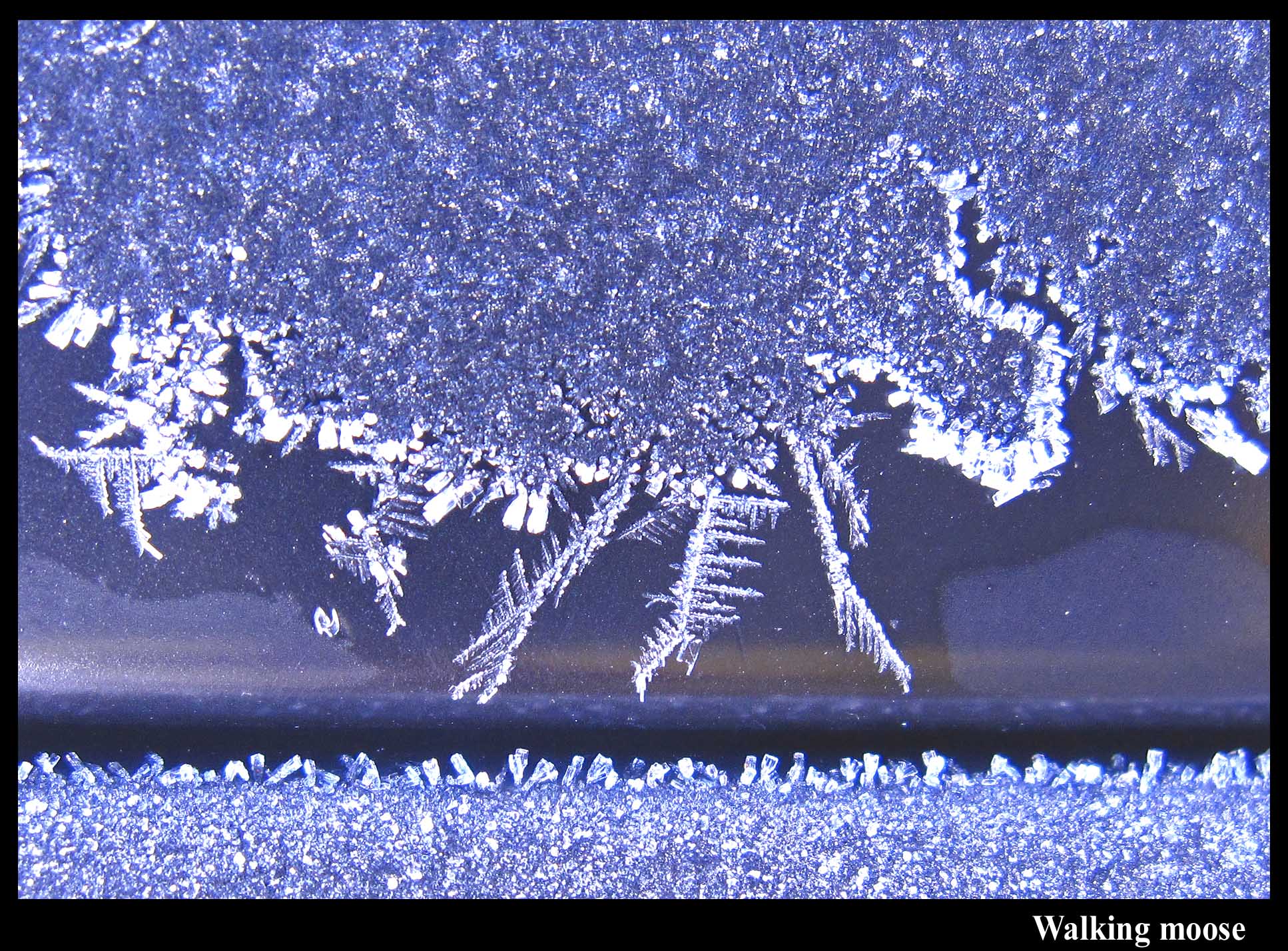

Awhile back, I posted frost that looked like an eye ("Eyes and Dry Moats" Jan. 22, 2010). Here are a few other forms:

A moose.

A tree.

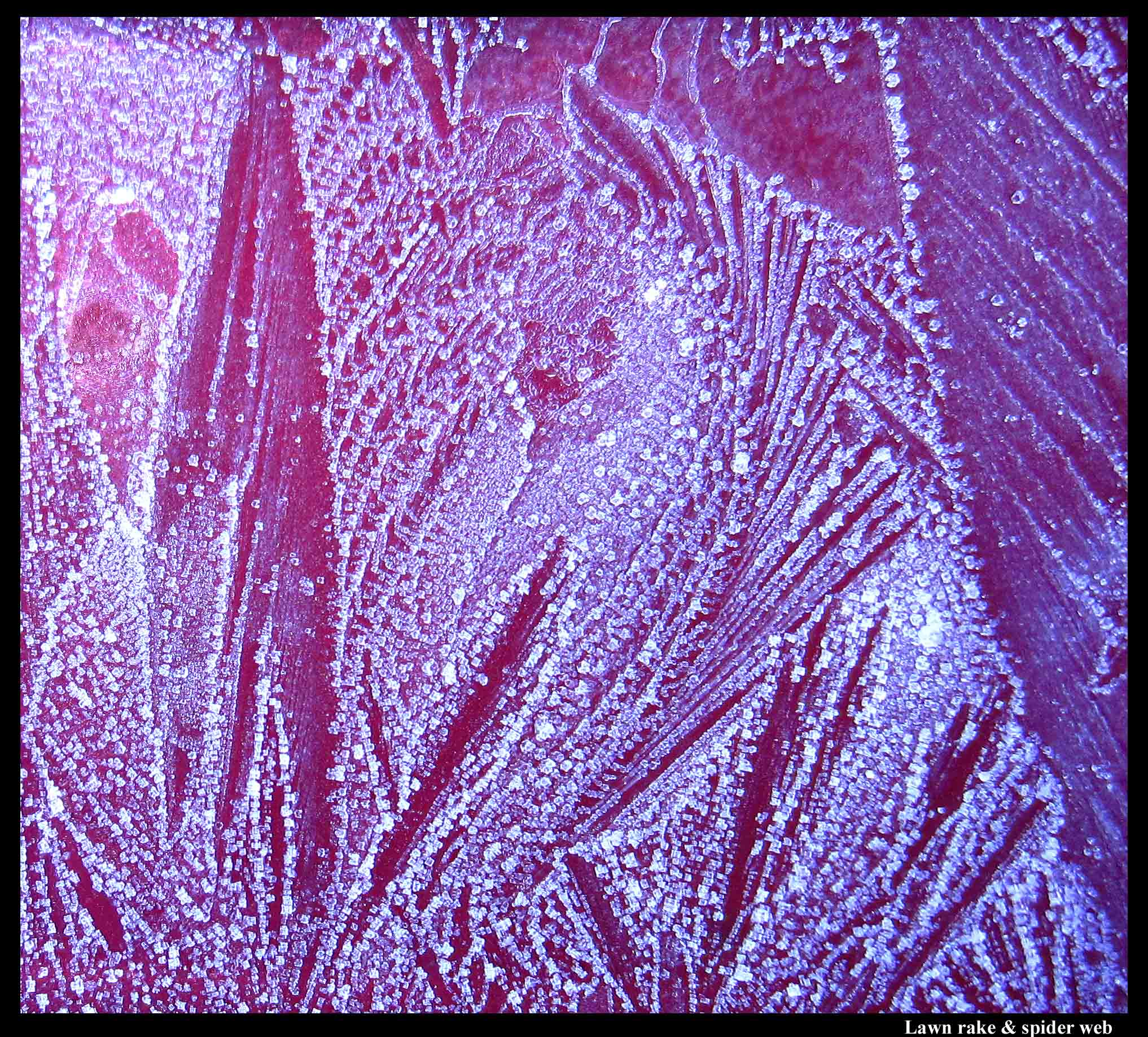

A lawn rake (or hand) and a spider web.

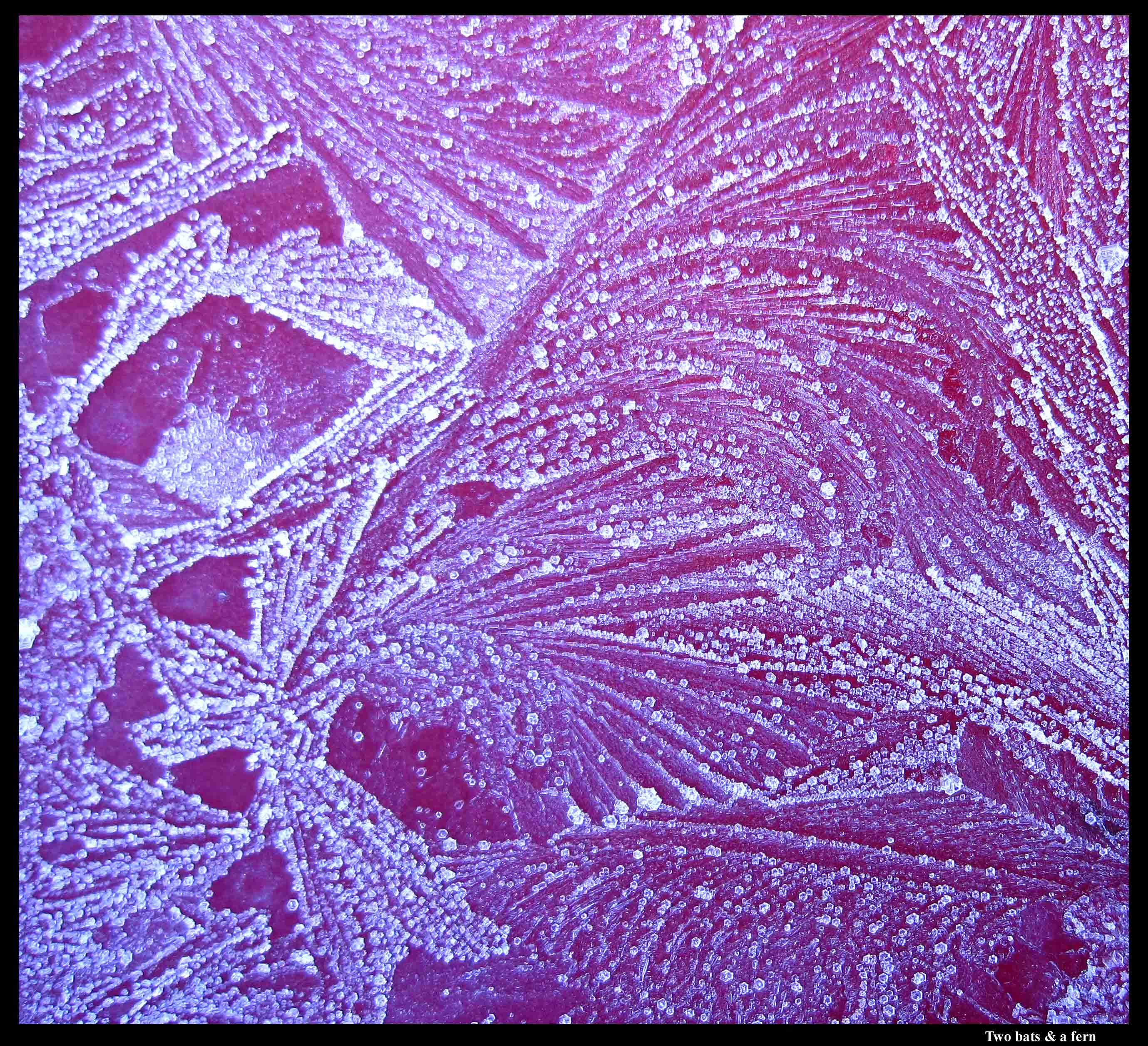

Two bats and some ferns?

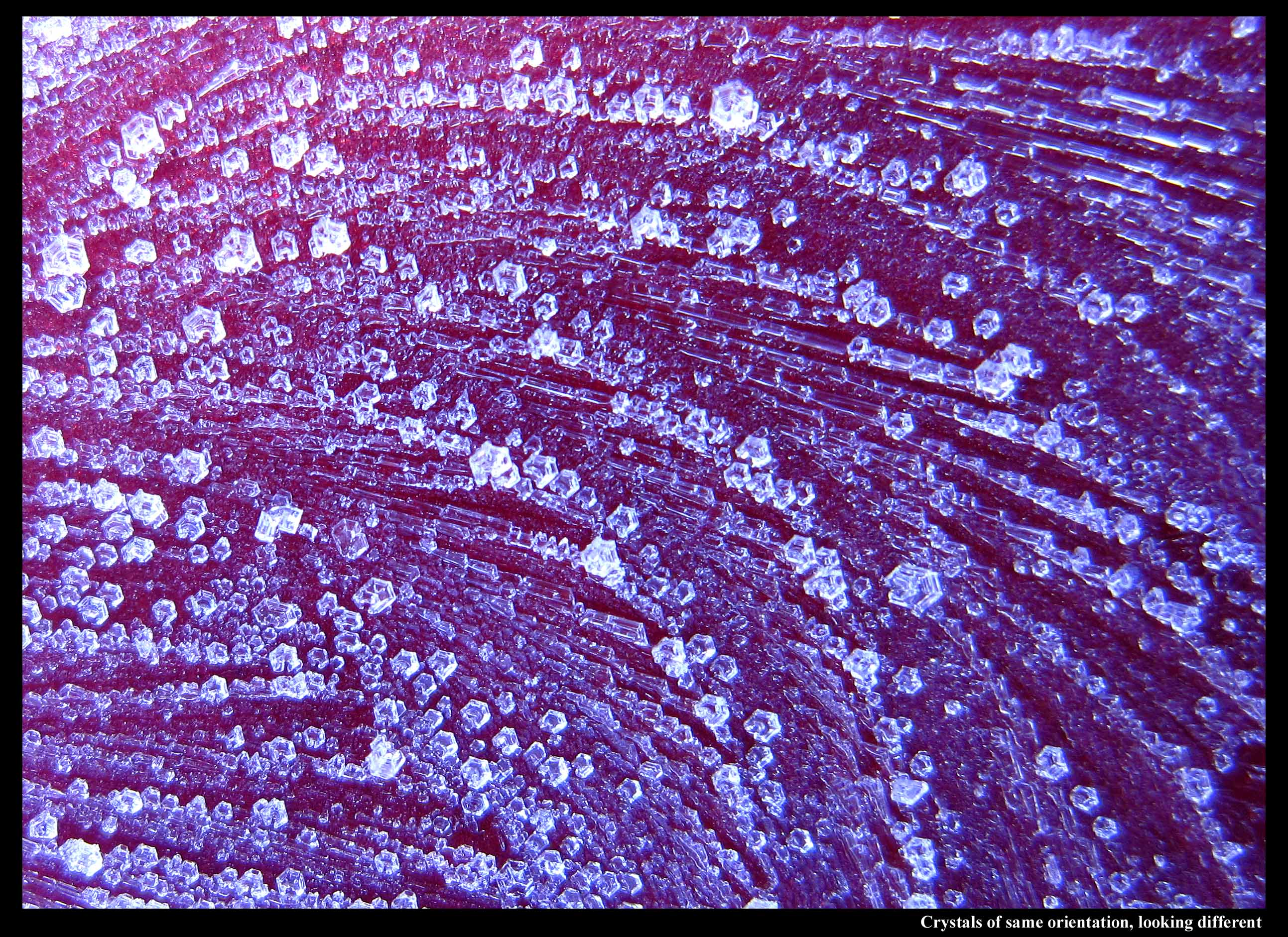

I noticed a few interesting things about the ferns in the above image. Look at the close-up below:

If you were to follow a line of crystals out one of the curves, and then take a ruler to the edges of the crystals, you will find that crystals at one end are slightly turned from crystals at the other. It's a slight effect, more easily seen in longer, curvy patterns, but it shows that when a finger of ice grew in the underlying water film, the crystal lattice actually twisted with strain as the finger curved. This was found out by experiments in the 1960s, so I was aware of this effect. But the other curious thing is that the line of crystals has two basic shapes: long but stubby ones and nearly hexagon-shaped crystals. They all have the same crystal orientation, but they look different. I hadn't noticed that effect before.

-- Jon

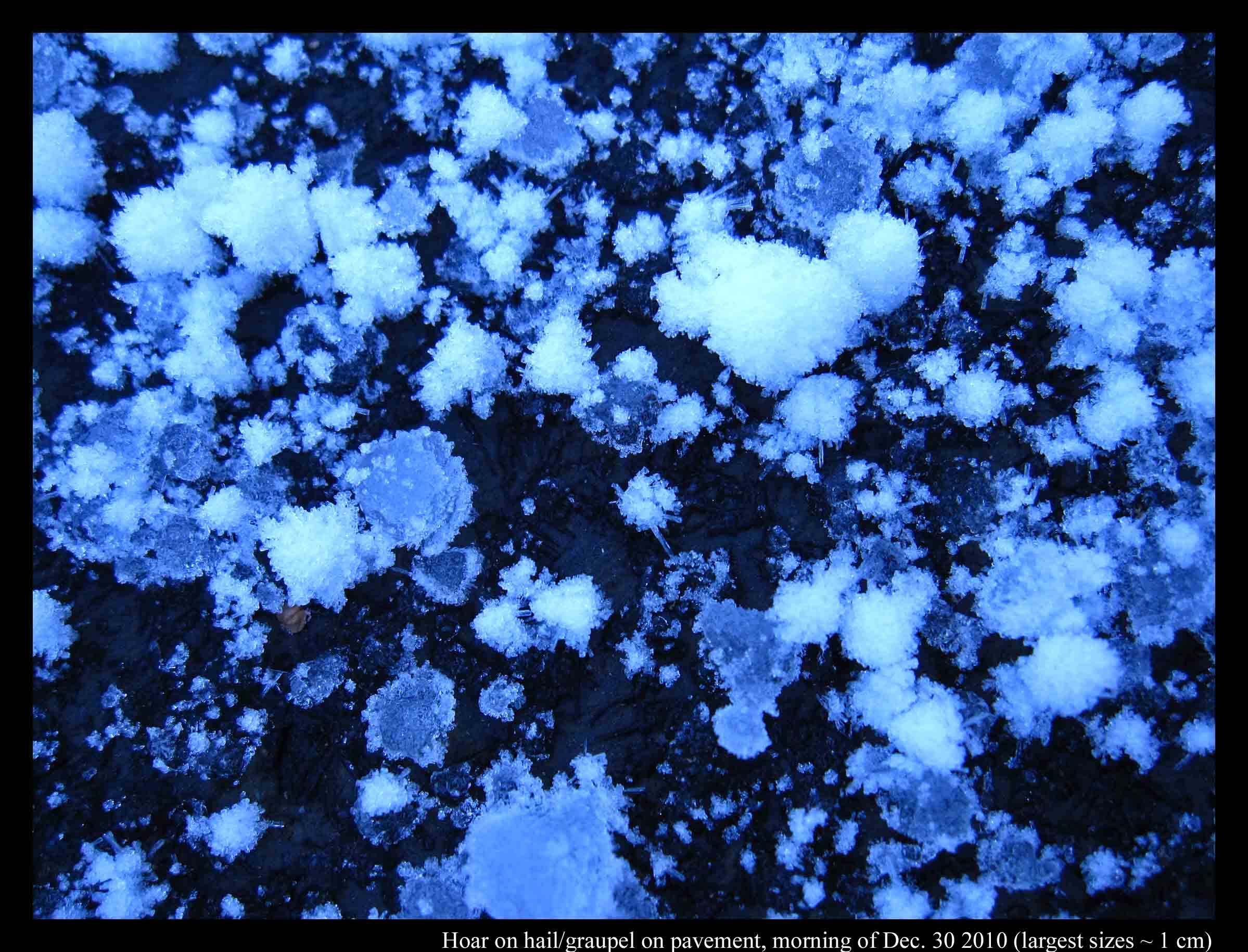

Hoared Hail and Coraline Cups

December 31st, 2010As far as I could tell, nobody had predicted hail last night, yet there it was on the ground, the largest hail I’ve ever seen here in the northwest. It fell on wet ground, freezing to the surface and then growing hoar columns, making the ground white and crunchy.

The parking lot in front of our apartment was covered in ice, mostly clear (i.e., "black") ice, yet, because of the ice lumps, it was not slippery under my boots. I kept expecting to slip, but never did. On the curb, where it was a little colder, the hoar was much thicker, looking like an inch of snow.

Same story for the tops of cars, where it had been coldest. The temperature was such that the hoar was mainly columnar. Columnar hoar, indeed all hoar, grows just like snow – when an excess of water molecules deposit from the vapor – and yet columnar hoar tends to develop more in the “cup” (C1b) and “scroll” (C1i) forms (see my Feb. 14 posting for the meaning of the symbols).

But unlike the pencil-like columnar forms of falling snow, these cups and scrolls grow broader at their growing end, even branching out into a pattern a bit like coral.

And if you look closely at the above shot, you will see that the “branches” grow along the same axis as the crystal from which they sprout. (For the above shot, I put a piece of black cloth in back to show the boundaries more clearly.) Such branching contrasts with that for tabular crystals, such as the ones on the familiar six-branched snow crystal.

Why do the columns widen at their growing ends, thus making a cup-shape, why do the cup rims sometimes curl into scrolls, and why do they branch out? I suspect the reason for all three (though not a complete reason) is that the humidity next to the growing crystals is very high – higher than that surrounding the typical column form that drops from the sky. Unlike the latter case, where the humidity is too low for the prismatic faces to grow outward, at least at any rate near that of the basal, here both the basal and prismatic faces grow at comparable rates. Such growth behavior also depends on the temperature, for reasons that still elude us.

- JN

BEDFISH: Revising an old Idea for Classifying Surface Ice Forms

January 31st, 2010It often seems like people refer to any kind of ice stuck on something as frost. If one looks in books or the Internet, one can usually find a specific term for the many different and interesting ice formations, but a term used by one group of people generally differs from that used by another. Wouldn’t it be nice for scientists and naturalists (at least) to have some generally universal, agreed-upon way to describe any surface-ice formation? Snow crystals have such a system, so why not surface-ice forms?

We could try to establish word-names for each formation, like “frost flower”, but different people are used to using different names for the same thing, and they are unlikely to give up the habit, particularly if they are unfamiliar with the language of the term’s origin. For example, there are several well-used terms for the ice columns in dirt that I discuss in “Ice on the Rocks” including “frost heave”, “needle ice”, "ice columns", and “pipkrake”. But “needles” also names a type of snow. Another example: The white, curly ice hairs that can extrude from plant stems and logs is sometimes called “frost”, “frost flowers”, “Ice flowers”, "needle ice", and “sap crystals”. But the two flower terms are also used for several other, very different things. Though a few terms seem to be used consistently in English, like “hoarfrost” and “icicle”, most aren’t. And probably none work across all languages. So, instead of using word-names, a set of symbols may work best.

Wilson Bentley gave a good start to such a universal code for surface ice way back in 1907. His article “Studies of frost and ice crystals” gave an ingenious method for classifying several types of surface ice [1]. The article is a fantastic source of information about hoarfrost, window-pane frost, and ice that grows in bodies of water like lakes and rivers. Unfortunately, I know of no one except Bentley who ever used his system. This lack of use is probably due to issues unrelated to his system’s merits, so his system might need only a little revision and some promotion to get it into use. My purpose here is to suggest such a revision.

Bentley’s system used three letters to classify many kinds of ice-forms:

Position 1: capital letter giving the kind of frost or place of deposition.

Position 2: capital letter giving the characteristic form of the ice.

Position 3: capital letter giving how common the ice form is.

Position one could be "W" for window frost, "H" for hoarfrost, "I" for window-ice, "M" for massive ice (e.g., ice in puddles, lakes, and rivers), and "S" for hailstones. For short, we could call it the WHIMS system. As an example, the following ice formation is “IFA” in his system.

Although the “I” stands for window-ice, ice on smooth black metal, as in the above case, has similar growth patterns.

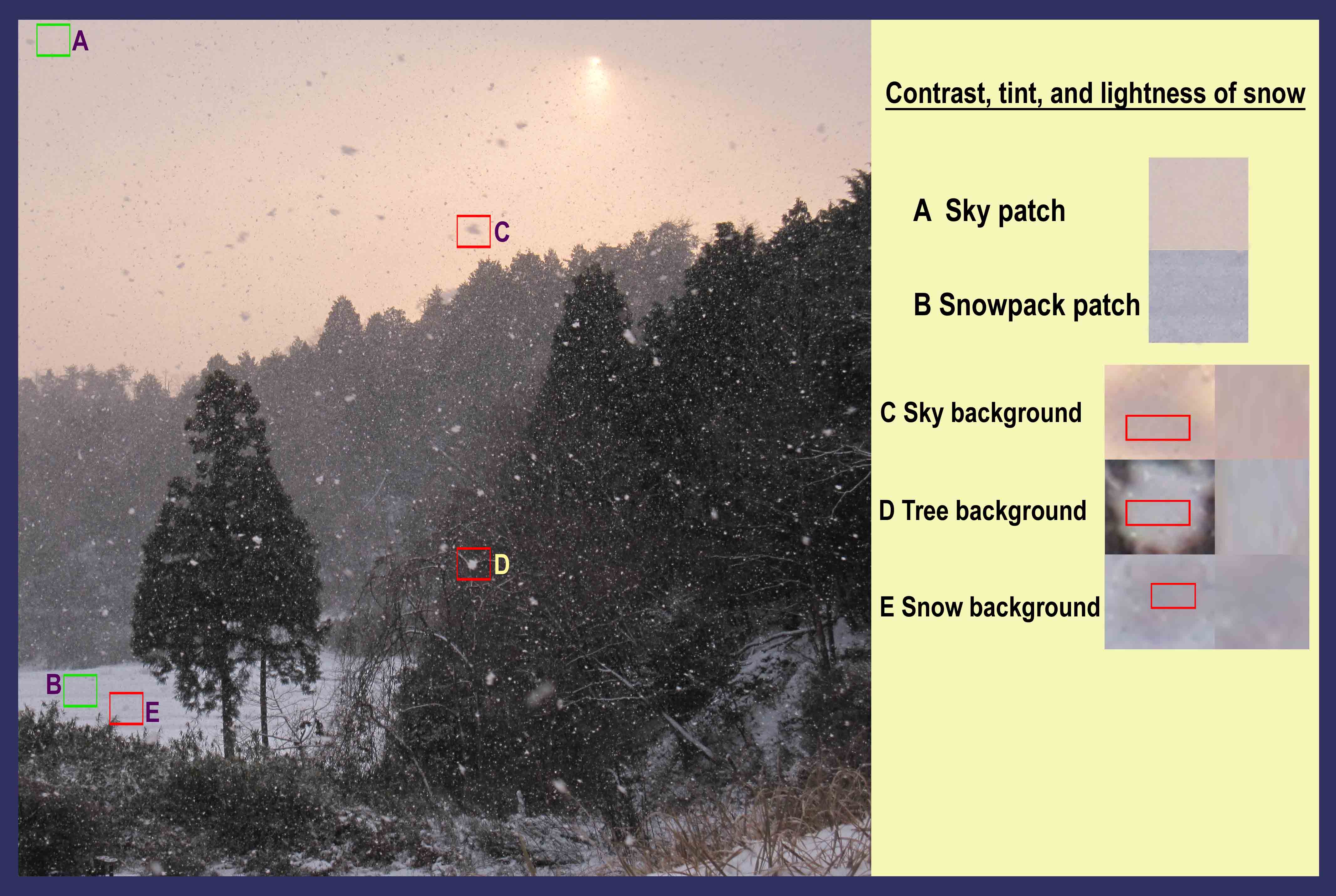

White Snow, Black Snow, Pink Snow, Blue Snow

January 3rd, 2010Hands down, my favorite book for browsing is M. Minneart’s The Nature of Light & Color in the Open Air. This small, easy to carry (and cheap if you get the Dover edition) book has 233 short sections on things one can see 'in the open air'; for example, twinkling of stars, the color of lakes, and the rainbow. Section 93 is on black snow, in which he notes how the apparent whiteness of a falling snowflake seems to change from blackish to whitish when the flake’s background changes from the grey sky above to a darker background below (such as dark-green trees). It is a simple enough observation, but I didn’t bother looking for it until a few years ago. Indeed, the illusion of whiteness change is strong. Look for it next time you go out when it's snowing.

On a walk on Jan. 2, I took the picture below because I thought the sun poking through the cloud was interesting, and then later realized that I could easily compare the whiteness of the flakes. Minneart's next section describes a related contrast illusion that also can be tested in the picture - the feeling that the snow on the ground is brighter (or whiter) than the sky above. See if you can shake this illusion next time you go out in the snow.

The sky in the picture is not uniformly grey, as Minneart assumes in his discussion, but is a yellowish-red at and below the level of the sun. So, for the comparison of the sky brightness to the snow brightness, I chose a patch of sky of sky at the place within the green box marked 'A' in the upper left, where the sky is darker. (To see this and other boxes, you can click on the picture to enlarge it.)

Ice of Hearts

December 28th, 2009Back when I lived in Boulder CO, I worked with Charles Knight on developing a new way to grow ice crystals for experimental study. I knew that the problem with most methods was twofold: there were too many crystals too close together to be able to learn how each one behaved on its own, and the surface that held the crystal would influence the crystal’s growth. Charlie hit on a great way to eliminate the first problem: put some water in a small pipette (like a narrow, tapering straw) and freeze the water from the wide end. At the tip, which stuck out into a small observation chamber, ice would grow out as a single crystal. Unfortunately, the smallest pipette tip was about a millimeter in diameter, which is too large. I then tried using Dupont hollowfill fibers, which are about 20 times thinner – about as thick as fine human hair. But this was still too thick. So I started using glass capillaries, which I could heat with a small torch to draw down to sizes 100-1000 times thinner than the pipette – about as thin as small cloud droplets before they freeze into ice. We had our method. From the start we would see things that hadn’t been reported before. Some of these things we (or I) published, but most of the things still remain unpublished. One of them is the heart-shaped crystals. The photo below shows the tip of the capillary, which is about 10 times thinner than human hair, along with a thin heart-shaped crystal.

After the heart grew a little more, it developed into a hexagonal shape. But probably the most bizarre thing I saw occurred when I decided, just for kicks, to try to evaporate ice from the inside of a crystal by connecting the wide end of the capillary up to a vacuum pump.

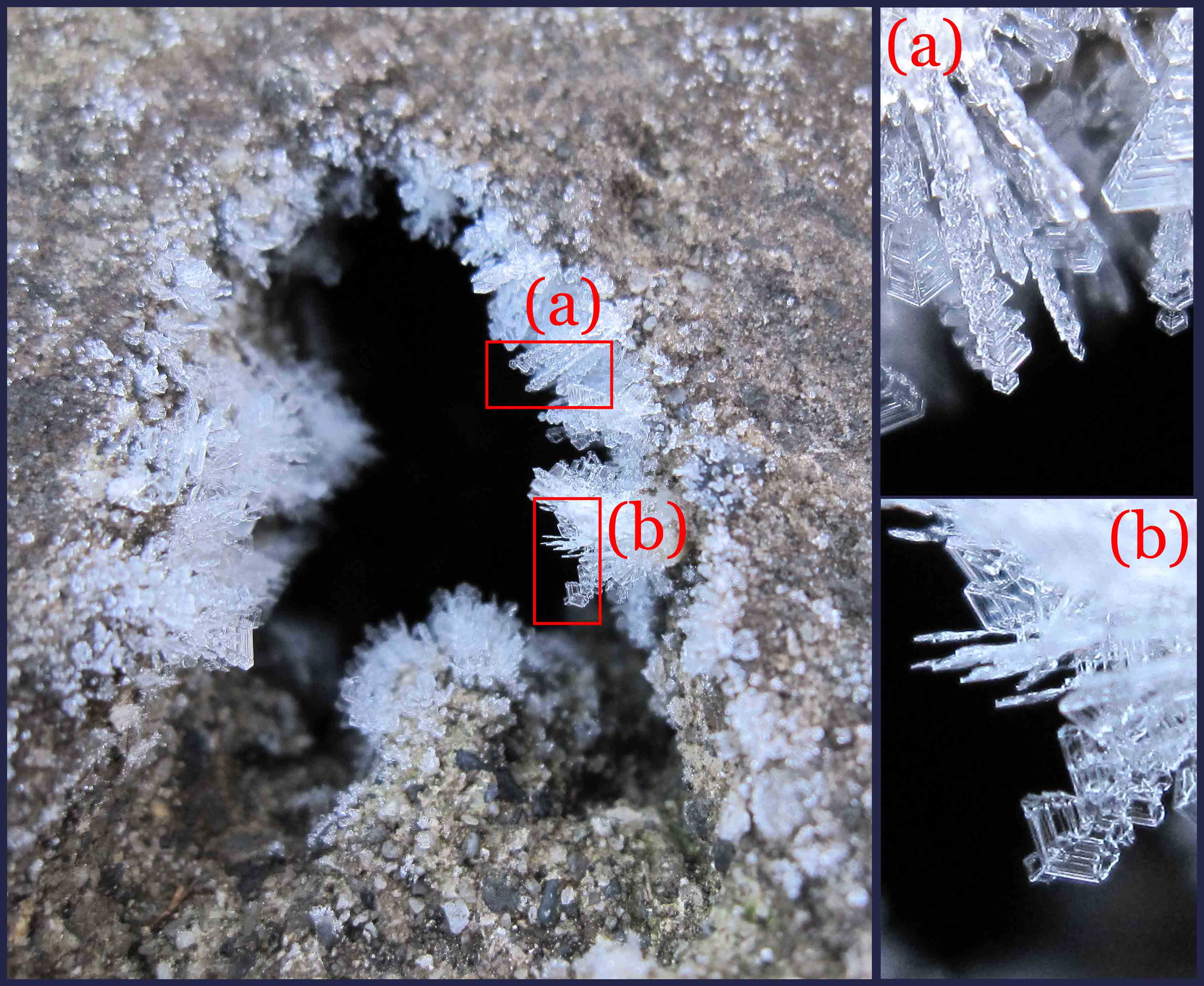

Hoar in a Hole

December 26th, 2009

Like snow, hoar can grow as a thin plate, a thin dendrite, a long column, a sharp needle, or some intermediate form, except hoar generally grows out in only one direction, not the six directions of the snow crystal. The ground surface here can dip slightly below freezing, but a short distance below the surface lies warmer, often moister, ground. At such temperatures (i.e., within a few degrees of freezing), both snow and hoar grow into platelike, or tabular, forms. Even when nearby blades of grass or foliage have columnar hoar crystals, the hole usually has tabular, showing that a small change of temperature changes the crystal considerably. (The dendrite, the most extreme tabular crystal form, grows at temperatures even lower than the columns.) (a) shows a few long, narrow crystals with jagged edges like a sawblade. And like a sawblade, these crystals are thin, as some of the side-views in (b) show.

-JN

Reflections off Falling Crystals

December 26th, 2009On my morning icespotting trip the other day (12/23), I caught a glimpse of an unusual sight - a sun pillar. I thought I saw one once last winter, but this one was unmistakable. It seemed more striking even than the one in Robert Greenler's book "Rainbows, Haloes, and Glories", a classic book on atmospheric displays. A line of light above the sun forms when sunlight reflects off the bottoms of falling crystals that fall a certain way - nearly horizontal. A pillar can form from either columnar crystals, oriented like a log floating on water, or tabular crystals, oriented like a frisbee in flight. For the reflection to reach our eyes, only the crystals that appear above the sun can reflect sunlight to our eye. So we see the reflections coming from the region directly above the sun, as in the picture. The same effect can occur below the sun, when the sunlight reflects of the tops of the crystals. I took this picture on the sunset setting of my camera, which boosts the reds, but the view to my eye was, if anything, more stunning.

-JN

It Came Out of the Sky

December 26th, 2009Our first snowfall this season came overnight with a howling westerly, but left just a light dusting. Only certain surfaces with a wide view of the sky were cool enough to preserve the snow. The only place in our yard was the roof of our car, which I've found in the past to cool about 8 degrees Celcius below that of the air at head-height. But looking out our window this morning (the 19th), I saw something else that came down - a spider. It might have come from the telephone wire about 30 feet above the car, or, with all the wind, might have blown in from a more distant place. We see these colorful spiders on their webs all over our yard and have come to view a few of them as familiar friends. The one near our front door last year seemed to freeze up and die when the first cold weather came, but later, after being warmed by the sun, popped back into action. I set this fallen spider out in a warm and dry spot, but alas, it did not recover.

- JN