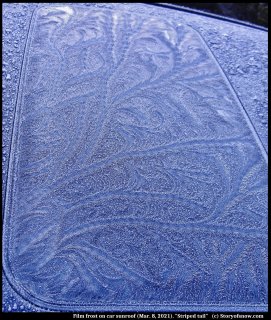

Category: "Hoar frost"

A greenhouse effect demonstration that you can feel with your hand

January 18th, 2023Probably most people consider the greenhouse effect as an important, yet subtle, effect on our climate. I suspect though that very few consider it the major effect on our daily weather, amenable to direct sensation, that it really is. Perhaps this lack of appreciation can be partly alleviated with a simple and quick demonstration. Below is my attempt at such a demonstration. This demo focuses on a key aspect of the greenhouse effect. It requires only items typically found in a kitchen yet allows one to directly feel the warming. An added bonus is that the specific phenomenon illustrated also helps explains other phenomena we witness in daily life. Below are all the things you need to do the demo. (click on any pic to enlarge)

What does the greenhouse have to do with snow?

But first, as this is a snow blog, what is the connection to snow? The growth of snow crystals is, except for their being in free-fall, almost exactly the same as the growth of hoar frost on the ground. The hoar frost on the ground occurs when the local greenhouse effect during the evening and night is relatively weak. That is, the local atmosphere above is cloud-free and relatively dry. (Of course, the air at the ground needs to be relatively cold and humid as well.) This connection illustrates one way we directly sense variations in the greenhouse effect through our weather. More on this later.

A key aspect of the greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect involves several connected concepts, or aspects, a fact that makes the complete effect much more challenging to understand than is commonly appreciated. Nevertheless, we can readily understand one of its crucial aspects: emitted infrared radiation (IR) from the atmosphere directly warms us on the ground. This IR radiation from above, also known as “back radiation”, is not small: indeed, averaged globally and annually, the radiated energy we receive from atmospheric IR is roughly twice that which comes from the sun. (Why do we not notice such a large effect? Because, unlike sunshine, it never stops.) Unfortunately, this is not how the effect is usually presented in the popular literature. For more details about this issue and other greenhouse misconceptions, I urge you to read Alistair Fraser’s excellent and amusing “Bad Greenhouse” page (1), but here I focus on a simple demo.

Simple demos of the effect

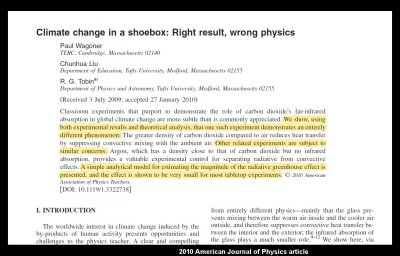

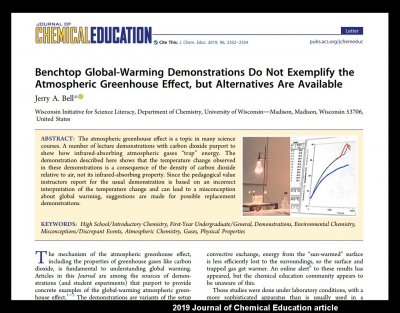

Most demos of the greenhouse instead focus on atmospheric absorption of infrared by greenhouse gases. Although absorption of IR is part of the greenhouse effect, to understand how we are warmed at the ground, one needs additional concepts to complete the explanation, concepts that are usually left out of the discussion. More to the point for this blog entry, of the demos that I’ve seen, all of them misrepresent the atmospheric greenhouse. Specifically, instead of illustrating a heating process in the atmosphere, such demos instead illustrate the heating process in a gardener’s greenhouse. This is the wrong effect. If you are skeptical of this claim, consider the highlighted text in the following study (2):

A similar study was published a few years later in the European Journal of Physics. But it is not just the physicists who think the popular demos are wrong, here is a similar study from chemists (3):

The title of that study should also make their point clear. Let me emphasize here that the demos that these studies criticize are actually the best available ones, for example the one use by Bill Nye, “the science guy”. A quick survey of other demos readily found on the Internet (refs 4-7) takes me to ones that are even less relevant to our atmosphere (sadly, even ones suggested by NASA). It is also unfortunate that even the above two studies use terms "climate change" and "global warming" in their titles, even though they are really about the greenhouse effect. These are distinct concepts, the former being about an increase in the latter. We are interested here only in the greenhouse effect.

As pictured in the first image above, all you need for this demo is a stove (or hotplate), a baking pan (if using the stove), oven mitts, new aluminum foil, a baking sheet (i.e., oven-safe paper), and a few teaspoons of vegetable oil. For extra safety, use protective eyewear. Total time needed once you have the pieces set out, is only about 15 minutes. No thermometer is needed because you can feel the warmth with your hand.

1) Set the baking pan on the stove burner, centered if possible.

2) Put a little vegetable oil in the center and press on a section of aluminum foil to cover the base of the pan as completely as possible (can extend over the edges). Use an oven mitt to press the foil flush against the pan.

3) Turn the burner on to “medium” and wait about 10 minutes for it to heat up.

4) While waiting for the burner to warm up, tear off a piece of baking sheet large enough to nearly fill the area of the pan. Set it aside.

Once the pan has warmed up (carefully touch an edge of the pan to check), the experiment begins.

A) Put your hand a few inches above the center of the aluminum foil. Does it feel warm? WARNING: NEVER TOUCH THE FOIL SURFACE! IT IS VERY HOT!

B) Now put a little vegetable oil on the aluminum foil and carefully drop the baking sheet on the foil, trying to set it down without touching the hot surface so it covers nearly all of the foil. With the oven mitt on your hand, quickly press the baking sheet down so there are no air gaps between it and the foil (this is the purpose of the oil).

C) Now, repeat A). Does it feel noticeably warmer? (Before the baking sheet starts to burn, please use the mitts to move the pan off the burner and turn off the burner.)

It seems weird that you can put a cool object (the baking sheet) between your hand and a hot surface to actually warm your hand. Nevertheless, your hand is warmer because the baking sheet is an effective radiator of IR, whereas the Al foil is a very poor radiator of IR. (This is why hot items are wrapped in foil to stay warm.) For this reason, the adding of Al foil to the pan likely made the pan even hotter--it reduced the capability of the pan to cool. With the oil between the pan and foil, and between the foil and baking sheet, all three were put in good thermal contact, exchanging heat via conduction and thus having essentially the same temperature. However, the the top layer (i.e., the foil in A, the baking sheet in C) cools by conducting to the air above, so the top surface will actually be slightly cooler than the pan. However, in general, the temperature of a hot object mostly cools by emitting IR, unless it is covered by a poor IR emitter like Al foil.

In this experiment, it is too easy to be fooled into thinking the foil is not hot because it does not feel hot a few inches away. However, if you touch it with bare finger, your finger will get a burn due to conduction.

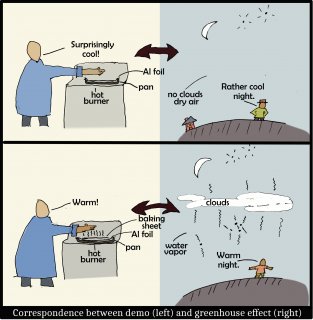

The following sketch shows why adding a sheet on top is analogous to the adding of greenhouse gases or clouds to the atmosphere.

In brief, the baking sheet, like greenhouse gases (including water vapor) and clouds, are very effective at radiating IR. The air in the atmosphere may be warm, yet is not radiating until greenhouse gases or clouds are present. So, on clear, dry nights, we are cooler simply because there is very little above us that radiates IR down.

Curved Film Frost, Part 1: On the General Causes

March 15th, 2022As I've seen it, the three most common ways to depict coldness in art and culture are the snow crystal, the icicle, and the curving frost on windows.

All of these have seen relatively little study, but without question the last has received the least. Indeed, I know of only three studies dedicated mainly to curving frost, and all three are over 50 years old.

It is perhaps little known that in terms of being observable to the typical observer, the third would likely be far more common. An odd thing to say? Well, people may say that they see it far less now due to the common use of central heating, or some might say that global warming is making it harder to form, but in these arguments they are wrong. I think the opposite: it is in fact far easier to see it now than maybe anytime in the past due to the ubiquitous presence of cars parked outdoors.

One curious thing about curved frost is its defining feature, the curviness. This feature contrasts with the straightness (and regularity) of snow crystals. What is the cause of the curviness in the former, as contrasts with the latter?

Bentley’s Most Singular Observation

March 2nd, 2022[This is the seventh and last in the series of re-posted articles, from 2012.]

You don’t have to look at frosted surfaces for very long before coming across something like the following.

The picture shows a large ice crystal amid a roughly uniform sea of tiny frozen droplets. Between the large crystal and the frozen droplets lies a clear ice-free zone, a dry moat around an island of ice. Sometime prior to 1907, the Vermont farmer Wilson A. Bentley took notice of this moat. Writing in the Monthly Weather Review in 1907, he wrote

"One of the most singular, and doubtless most important, phenomena that occur in connection with the formation of window frost is this: The true crystalline varieties of window frost ordinarily, apparently, repel the minute liquid particles or droplets of water that frequently collect like tiny dew-drops on the glass, and freeze in granular form thereon."

The Snowflake’s Closest of Kin

February 21st, 2022[From 2006 through 2012, I contributed annual articles to the annual newsletter "Snow Crystals" for the Wilson Bentley Historical Society. That newsletter is no longer available, so I will repost my articles here, starting with this one from 2006.]

Wilson Bentley is well known to readers here for his photomicrographs of snow crystals. Snow, however, was only one of the many ‘water wonders’ that held his fascination (ref. 1). Some of these wonders were made of liquid water, such as dew, and some, like the snow crystal, were frozen water (ice).

The frozen type he called “The snowflake’s closest of kin”, and they included hoarfrost, rime, windowpane frost, and ice flowers (2). To obtain photographs of any of them with the quality obtained by Bentley is difficult even now, which is yet another reason to admire Bentley’s skill and perseverance.

On the inside, these ‘kin’ all have the same crystal structure. But they appear different on the outside, largely due to the different ways the water in the surroundings gets to the ice surface. There are many distinct kin because the surrounding water can be in various states (i.e., ice, liquid, and vapor) and there are many ways that each state of water can get to the ice surface. I’ll focus here on snow crystals, hoarfrost, rime, windowpane frost, and ice flowers. These forms are commonly seen by many of us, and have been observed by people for a very long time. So it is easy to think, as I probably once did, that they are well understood by science. But this view is quite mistaken. Yes, we know they all consist of H2O molecules and we know something about the structure of ice, but how exactly they form contain many mysteries. I’ll describe briefly what Bentley thought of them, and what I think is known and not known about them.

A Stroll on a Mildly Frosty Morning

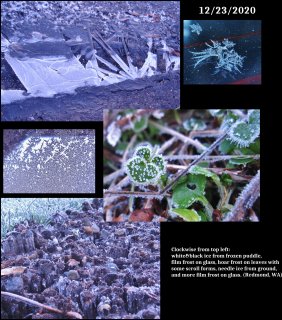

December 23rd, 2020So far this winter, we've had few frost days in the Redmond, WA area. This morning was typical of the half-dozen or so: a very light dusting of hoar crystals on the roofs and grass. One cannot expect much, and yet I am rarely disappointed. Indeed, it is not until I get close to some icy thing do I notice anything interesting. Sometimes, I still don't notice until I've clicked a few closeups and then viewed on a large computer screen. Here's what I found on this morning's stroll:

The frozen puddle showed some curvy meniscus lines and some straight ice blades, which I've discussed before. The film frost is more mysterious still, but the main curvy pattern is due to the freezing of melt (not vapor deposition, though some of this does occur). The hoar frost shows some scroll crystals, which I recently addressed in an article (no mechanism had previously been argued, but we propose an explanation). See the crystals on the leaf at upper right for the best examples of scrolls, though the details are yet a bit too small. The needle ice is the phenomenon responsible for the crunchy dirt and pushes ice up from the bottom. The ground is warmer below the surface, and here the liquid migrates to the ice front, pushing it all skyward.

Anyway, that's it for this post. No detailed explanations of anything. If you would like to see such explanations, click on the appropriate category in the archives at the right side.

And here's hoping you have a nice, frosty Christmas, wherever you are-

--JN

Hoar Frost on Plastic

February 17th, 2020The pattern of hoar frost depends on not just the current and prior conditions, but also on the surface. If the surface is less attractive to water, that is, more hydrophobic, then the hoar crystals tend to be more further spaced apart.

Or even more widely spaced apart. (Click on an image to enlarge it.)

These two images show hoar frost on plastic surfaces (garbage bin lids). If you look closely at the above picture, you will see that the hoar columns are growing off little mounds. These mounds are frozen droplets. You'll also notice that the directions of the ice columns are not random, but instead a given ice column tends to be pointing in nearly the same direction of its neighbors.

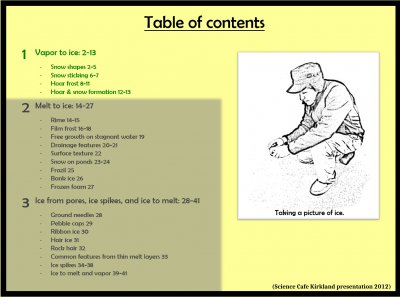

The Curious World of Ice and Snow: Part 1 of 3

February 4th, 2020In 2012, I gave a "science cafe" talk with a local series sponsored by the Pacific Science Center, KCTS public television, and Science on Tap. The title was "The curious world of ice and snow". The location was a bar in Kirkland, but open to all ages. When I showed up with my family, they tried to seat us in the backup room, the regular room having filled up, but I said "Oh, well I'm the speaker" and they kindly created a space for my family in the regular room. I was indeed surprised at the crowd. People are apparently more interested in ice than I thought. (Hmm, but where are they when I post here?)

Click on any image to see an enlargement.

The basic structure of each talk was to give a lecture of about 30 minutes and then allow up to an hour (I think) for the Q&A. In my excitement, I had created 41 slides, in retrospect too many for the allotted time.

Given all the time spent preparing the slides, I hope that by posting them here that even more folks can enjoy the images and discussions. But, instead of unloading all of them on you at once, I will break the discussion into three sections. By adding the following table of contents, each section will have 14 new slides and the total will be 42, which according to Douglas Adams* is a really special number.

The contents of this section is part "1", written in green font.

Martini Hoar (raise a tiny glass?)

October 19th, 2019The hoar-frost crystal shoots up like a thin, solid straw, then suddenly opens up into a cup-like shape. I have seen it often enough to give it a name: "martini hoar".

The cup can be weirdly segmented and polyhedral, but it nevertheless widens suddenly. Here are a few more (Sorry for poor photos—someday, I hope, I'll get better about photography.)

Here is a larger view of the region. Note the similar hoar coming down from the top, but without a clear view of the base.

This sudden widening feature has bothered me for awhile, but I was delighted the other day to figure out a plausible reason. My delight was made even greater because the reason involved measurements I made in the lab two decades back. The measurements were to understand snow-crystal habit, but apply equally well to hoar frost because hoar grows just like snow except it is attached to the ground.

Now that I have viewed some of the older pictures I took, the actual growth phenomenon looks more complicated in terms of crystal shape, so I am not so sure my reasoning explains things so simply. Nevertheless, it should apply well to many cases, and at least is worth learning because it involves important growth principles that also apply to snow.

Puddle gets its grooves (upon freezing), part I

February 16th, 2019These grooves appear on the surface of frozen puddles.

Most grooves are straight lines, and most of these also appear to have relatively symmetric sides, such as those marked #s 1, 2, & 4 in the above image. But some, such as #3, have sides that are much wider. Grooves can intersect each other at a "T" intersection, such as #1 and #3, or they can cross, as a 4-way intersection as in #2. Some, such as #4 start and end on nothing apparent and intersect no other grooves.

Sometimes the sides show small steps or sub-grooves, particularly on the wider sides, such as on #3. On grooves that curve, such as in #1 and #2 in the image below, one side can have a fern or foliage type of texture.

Film frost grains and radiative cooling of the ground

December 10th, 2017December 8th brought the first frost to the Seattle area. This doesn't mean that this is the first time this season that the ground reached 0 degrees C or lower. True, we had gotten snow in late November, though this by itself doesn't mean the ground reached 0 C because snow deposition differs from frost formation. The snow was below zero when it formed in the air, but for the rest of its existence, it could have been melting and the ground itself likely sped up the process by remaining slightly above 0 C. But in contrast with the snow, for frost to form, the ground itself must cool below 0 C.

When I used to put out some metal plates with recording thermocouples, I didn't see visible frost until about -5 C, but that was based on just a handful of measurements. Anyway, what this means is that we may have had a few mornings with some patches of ground (including anything connected to the ground) dipping slightly below zero but with no obvious frost appearing. Also keep in mind that "ground temperatures" reported at weather stations are 1.5-2.0 meters above the ground, and thus may be 5-10 degrees C warmer at night than some ground patches. Why? At night, the ground cools by radiating, and if the atmosphere is not radiating much down, then considerable cooling happens. This is why clear nights are the ones with the most frost or dew.

Anyway, here is one shot of some of this "first frost" on my car window.

The image shows patches of different texture. These regions differ in texture because they are tiny hoar-frost (i.e., vapor-grown) crystals of differing size or orientation. That is, they stick up differently in different patches. They stick up differently because they sprouted off of a thin layer of film-frost that had a different crystal orientation. So, the patchy look comes from the different grains in the film-frost. See some of my previous posts with diagrams about this phenomena (category: "film frost"). Here is one with particularly helpful diagrams.

http://www.storyofsnow.com/blog1.php/choppy-waves

-- JN