Category: "Snow Science"

A Change in Habit

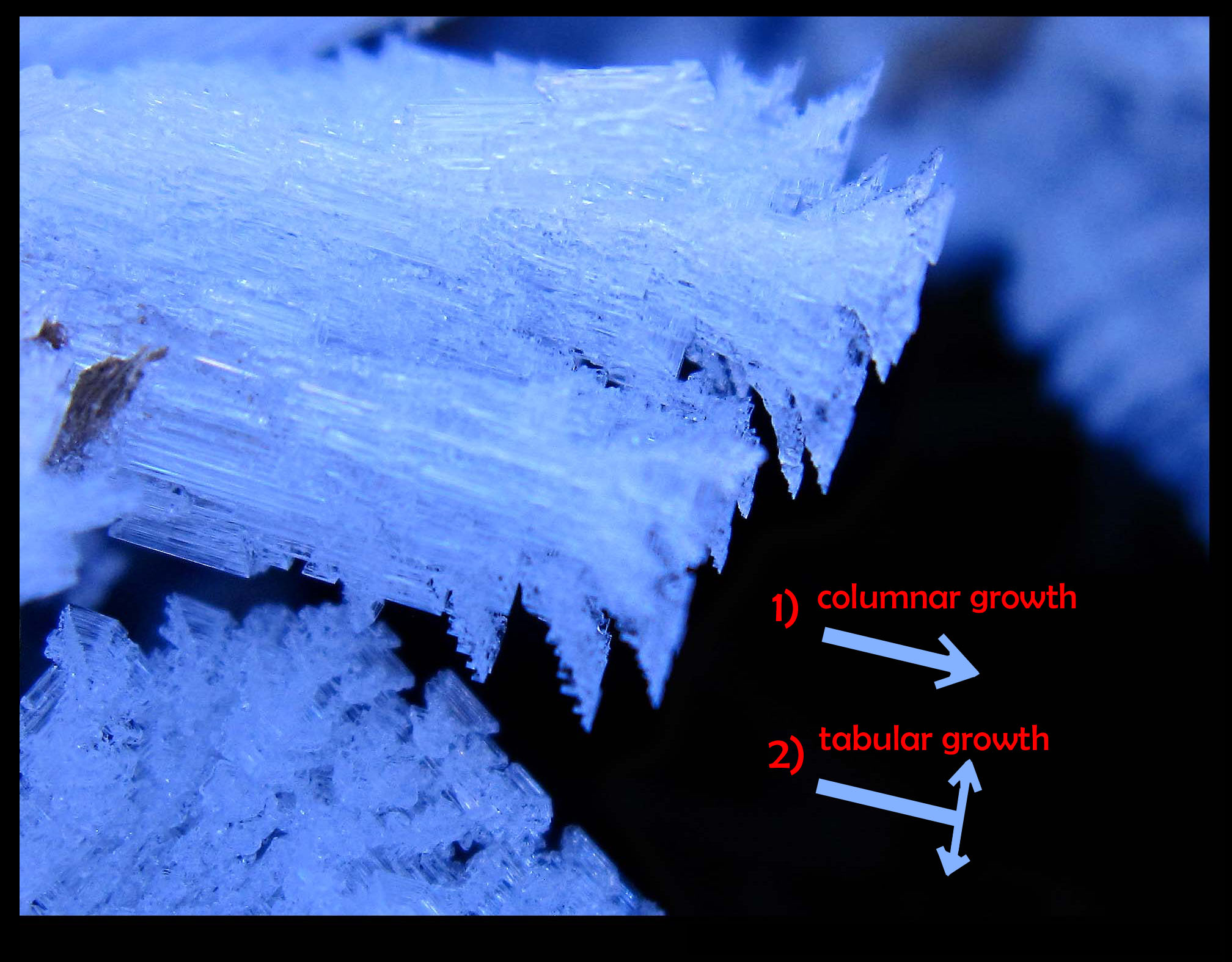

November 23rd, 2014The two main growth modes of snow and hoar (i.e., ice growth from the vapor) are columnar and tabular. In columnar, the shape is long and thin, like a pencil or cluster of pencils (bound snugly with a rubber band). In tabular, the shape is plate-like or fan-like. When a crystal form has an easily expressed shape, like a column or plate, we say it has a certain habit.

In hoar frost that had been growing for several nights, I saw some that had changed their habit.

On the first night, when the vapor was more plentiful, large columnar forms appeared. This habit grows between -3 and -8 C. On a subsequent night, the temperature got colder, below -8 C, leading to tabular growth. More vapor exists out near the ends, so this is where we see the tabular habit.

The arrows above show the fast growth directions. There is a transition that sometimes happens when both of the main growth directions are fast, making a flare, or trumpet-horn shape (other times, it may be more of a cup or vase). Such a transition is far more common in hoar than in snow, because, I believe, hoar on the ground can experience a much higher excess of vapor.

The dark region in the background is the water of a creek.

--JN

New habit diagram for branched tabular crystals

August 24th, 2014You might call these “snowflakes”. But let's be specific here with the names.

Anyway, a close associate who has been sweating over his snow-crystal growth machine in Japan for many years has just published his latest results. His machine is a vertical supercooled-cloud wind tunnel, which is like a thin column of cloud in which one can observe a single floating crystal. The crystal is in a climate-controlled box containing a droplet-infused stream of uprising air.

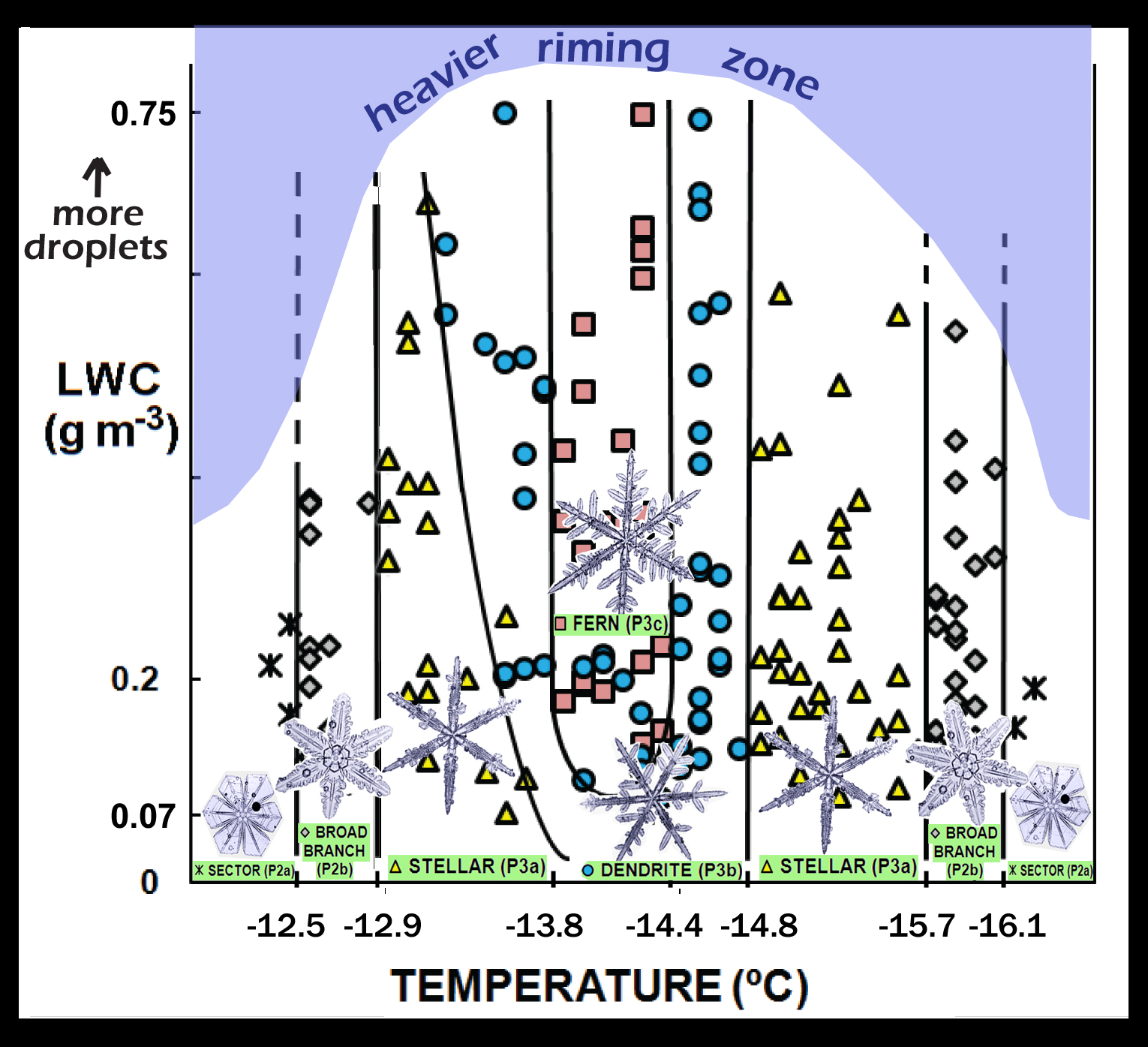

For this study, he focused on the crystal habit (i.e., shape) in the temperature range that we tend to get the large six-pointed stars. In addition to varying the temperature, he varied the density of droplets in the air. Nobody had done this before, certainly not as carefully and complete as he. Though he found lots of interesting results, I'll focus here on the following diagram:

Given its similar layout to the well-known Nakaya habit diagram, let's call this the Takahashi habit diagram. Whereas Ukichiro Nakaya showed us the crystal shape as he varied the temperature and humidity, Prof. Tsuneya Takahashi varied the temperature and droplet density (“LWC” on the vertical axis stands for liquid water content).

The basic findings: As the temperature decreases from left to right in the diagram, the crystal form goes from the very wide-branched sector crystal (see the “sectors”?) to the longer branches of the broad-branch crystal, to the even longer and narrower branches of the stellar crystal, to the crystal with sidebranches on each branch, called a “dendrite”, and then the pattern reverses back to sectors.

In the middle of this temperature range, something else happens. If he increased the density of cloud droplets in the dendrite regime, he got the more finely sidebranched fern forms. Ferns differ from dendrites only in the number of sidebranches they have. Fern crystals look more like fern plants because they have more offshoots. But at other temperatures, adding more droplets did not change the crystal form. In fact, the crystal size did not increase with more droplets, although the mass did increase.

If you observe some crystal that looks similar to one on the Takahashi diagram, you may infer that it grew under the indicated conditions. But this is not yet the final story: for instance, the amount of sidebranching is also thought to depend upon the temperature and humidity fluctuations. More fun ahead!

- JN

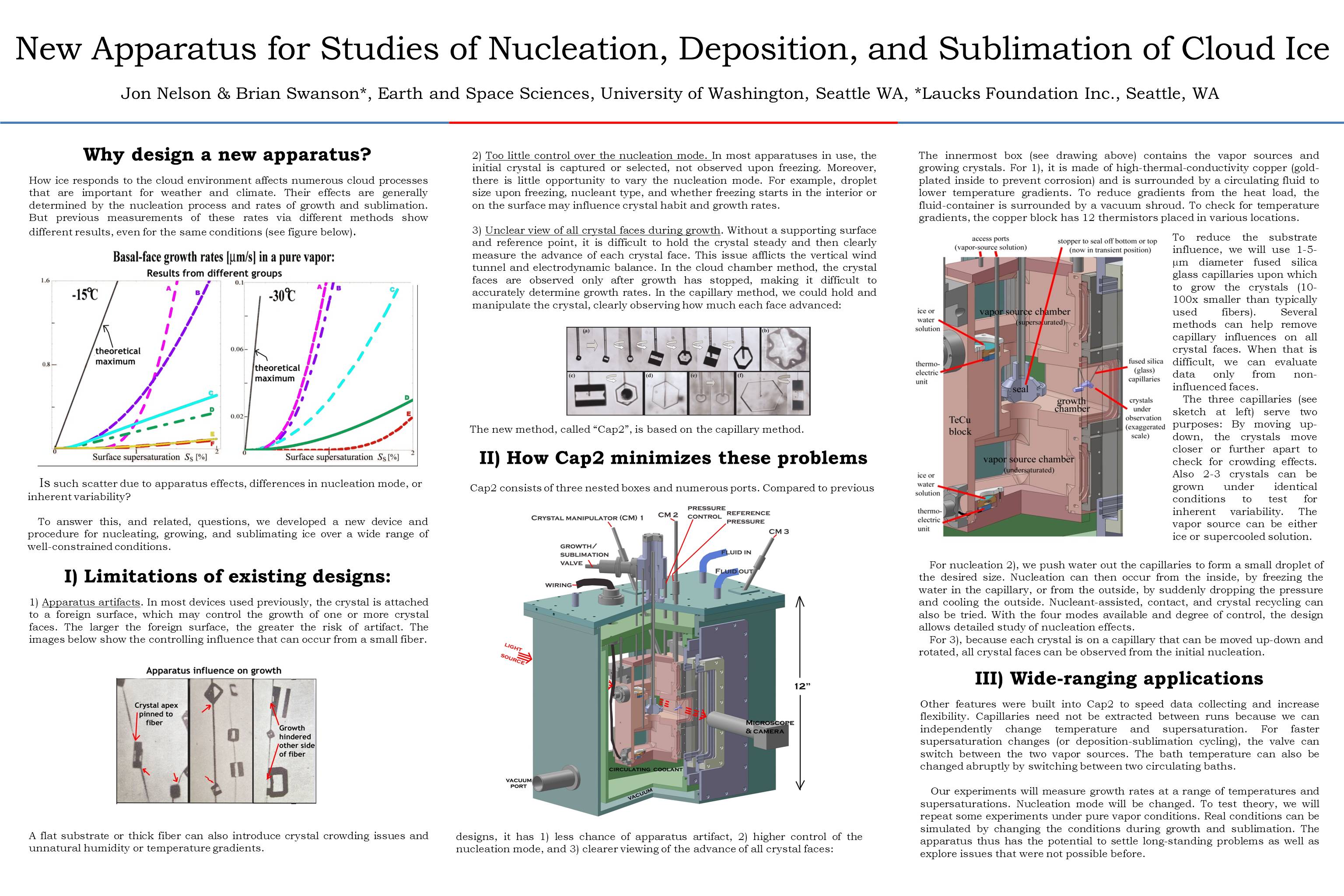

The new ice-crystal-growth apparatus

July 1st, 2014After a few years in the making, our new device for growing single ice crystals in a well-controlled laboratory environment is nearly ready. We are just adding a few small accessory pieces to allow us to start testing. I was to describe the apparatus at the cloud-physics conference this month in Boston, and made a poster to present, but decided to opt out. But, having spent a few days making the poster, I present it below.

As with all images here, click on image to see large-scale view.

And below is the same, but in blog format.

Halo in the sky? Uh, I don't see no halo...

April 20th, 2014After a few days of fine bright spring weather, the barometer falls and a south wind begins to blow. High clouds, fragile and feathery, rise out of the west, the sky gradually becomes milky white, made opalescent by veils of cirro-stratus. The sun seems to shine through ground glass, its outline no longer sharp, but merging into its surroundings. There is a peculiar, uncertain light over the landscape; I 'feel' that there must be a halo round the sun!

And as a rule, I am right.

The quote, from Minneart* describes a common ice-related atmospheric apparition. It appears in skies all over the world far more often than the rainbow, yet few notice it. As a graduate student, I read about halos and often looked for one, but didn't notice it myself until someone else pointed it out. As a post-doc in Boulder, I was out walking with Charles Knight, and I mentioned my lack of success. He glanced up near the sun, pointed, and said “why there's one right now”.

What I had missed in my readings had been the fact that most halos are rather indistinct and often incomplete circles. Indeed, now when I point out the most common one (the 22-degree halo) to someone nearby, they often don't see it. But occasionally, it is sharp enough (and colored) to the extent that anyone will see it if they bother to look up and glance toward the sun. And often it occurs with other ice-crystal apparitions that are even more obvious.

Last fall, while perched high on a rock face, belaying my partner up**, I saw such a vivid display.

The bright spot is called a “sun dog”, “mock sun”, or “parhelia”. They, one on either side of the sun, usually appear together with the 22 degree halo. Indeed, the sun dogs very nearly mark the spots where that halo intersects another arc called the parahelic circle. Their cause: horizontally oriented, tabular ice crystals.

The fun of shooting down your own theories

April 10th, 2014Thomas H. Huxley once wrote the famous line:

The great tragedy of Science: the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.

Great man, catchy phrase, but perhaps a bit overdramatic. To me, the slaying of a “hypothesis” (i.e., pet theory or just idea, really) can be the beautiful thing. It means that one can do a lot of damage with just a simple observation. I like it, even when I'm shooting down my own theory. Here's an example:

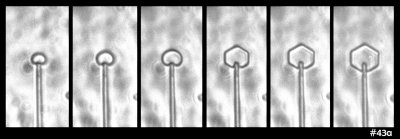

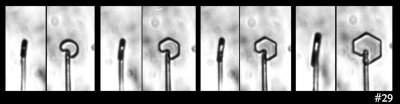

Some time ago in my experiments, I saw the following ice growth sequence:

What you see there is an extremely small, thin ice crystal growing from the tip of a glass capillary into air. (Size-wise, the glass capillary is about 5 micro-meters in diameter, or about 1/10th the thickness of the hair on your head.) I saw it happen several times. As the crystal grew, it developed the prism facets that generally define the hexagonal crystal shape. Other people had seen such rounded growth before, generally within a few degrees of zero (C), though in all cases, the crystal had been extremely thin. You can also see this thin, rounded (non-facetted) form in some hoar-frost formations.

The mystery here is why the disk grows without the prism facets for awhile. I never saw this with thicker crystals, so I formed a little theory. The theory involves the source of the water molecules to the curved region of crystal: some come from the vapor in the air and some wander over from the flat, non-growing crystal faces on front and back. In the 1960s, people had tried to measure this “wandering distance”, but never determined a consistent value. My theory predicted that once the crystal thickness exceeded about twice this distance, the curved edge would transition to flat, giving rise to the hexagon.

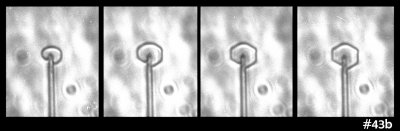

But then I looked closely at this case:

That sequence shows the side and front view. The crystal doesn't discernibly thicken when the flat prism facets appear. Zing! That theory shot down.

On to the next pet theory. So maybe the key factor is the diameter of the disk: One might argue that the curvature of the crystal surface must be below a certain value, which means a large enough diameter is needed, for the flat facets to appear. Or, the size of the resulting prism faces must be larger than that needed to have several surface steps (which help ensure flatness).

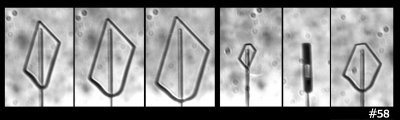

But then I look at this case:

In that case, I see both smaller and larger prism faces forming at the same time (same thing can be seen in the previous image). So, I guess the curvature or size of the resulting face is not the main factor. Zing!

Some researchers had observed slight bending of the prism facet above -2.0 C in equilibrium. They postulated a “roughening temperature” at -2.0 C. This might explain the rounded disc edge, but wait! 1) This disc edge becomes facet as it grows, so it is not merely temperature, and 2) these crystals are below -2.0 C.

Zing again!

Well, there are always “impurities” to blame! Crystal growers are fond of blaming some trace, active chemical, or “impurity” for inexplicable results, so we could theorize that the above show the effect of surface impurities. As the crystal grows, the area over which the impurities distribute increases, thus diluting their concentration, and thus reducing their effect. Yes! This could explain these results.

But, wait, what about this:

The above shows two sequences (same capillary) in which some prism facets have formed, but some remain round. In the right-side case, one corner even rounds as it grows. Hmm, not a likely result of impurities. Zing!

So, I am down to one last theory. I do not yet have the data to shoot it down. And I'm not telling you, or I'd ruin the fun. We just need more data.

All in all, I think Huxley needs a little tweaking to serve my view:

The great beauty of science: the slaying of a pet idea by a simple observation.

-JN

The cup and the butterfly

February 25th, 2014In early January, while visiting a cold, dry region, I saw this frost on a wooden fencepost.

The pattern resembled a cluster of butterflies. In the shade, these "butterflies" were blue, reflecting the blue sky. In the sun, they were bright white:

These are a type of hoar-frost, and though hoar-frost grows by the same processes as snow crystals, they can take on an even greater variety of forms. That they have more forms is a consequence of the fact that they can experience much greater levels of humidity, that is humidity relative to their temperature. This greater degree of humidity produces faster growth. Frost forms can also be more unusual because the proximity of the crystals alter the vapor gradients.

Bending of branch and pond

February 11th, 2014Bending bending bending

The fir branches are bending

They are waiting for more snow

The famous Japanese poet Basho wrote a poem like the above, except it was about bamboo bending under the snow load.

I was reminded of Basho's poem yesterday, as we just had our first snowfall of the season. Here in Redmond, about 2 inches, just enough to bend some of the fir branches.

And not only the branches were bending.

I took the opportunity to check out the pond. It had an ice covering before the snow, but with the snow and warming trend, the ice had thinned, and gotten pressed down under the snow load. The glaze over the pond was bending. Where a hole appeared in the ice, water got pushed up and out, flowing in dark channels over the icy glaze, forming a spider-like or branch-like pattern in the now slushy snow. I climbed up a tree on the shore and took a few shots.

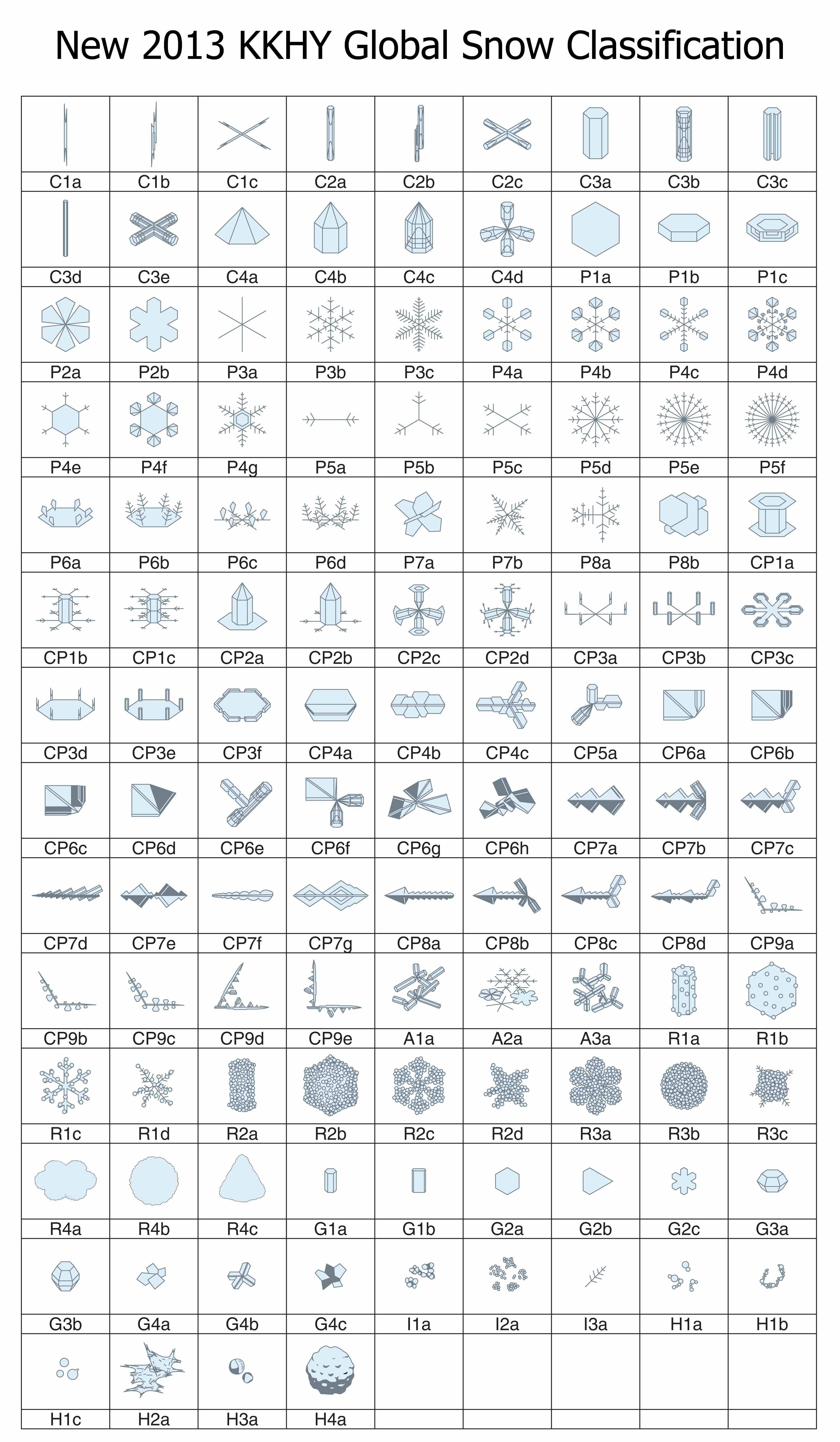

One hundred twenty one forms of falling ice: the new snow classification system

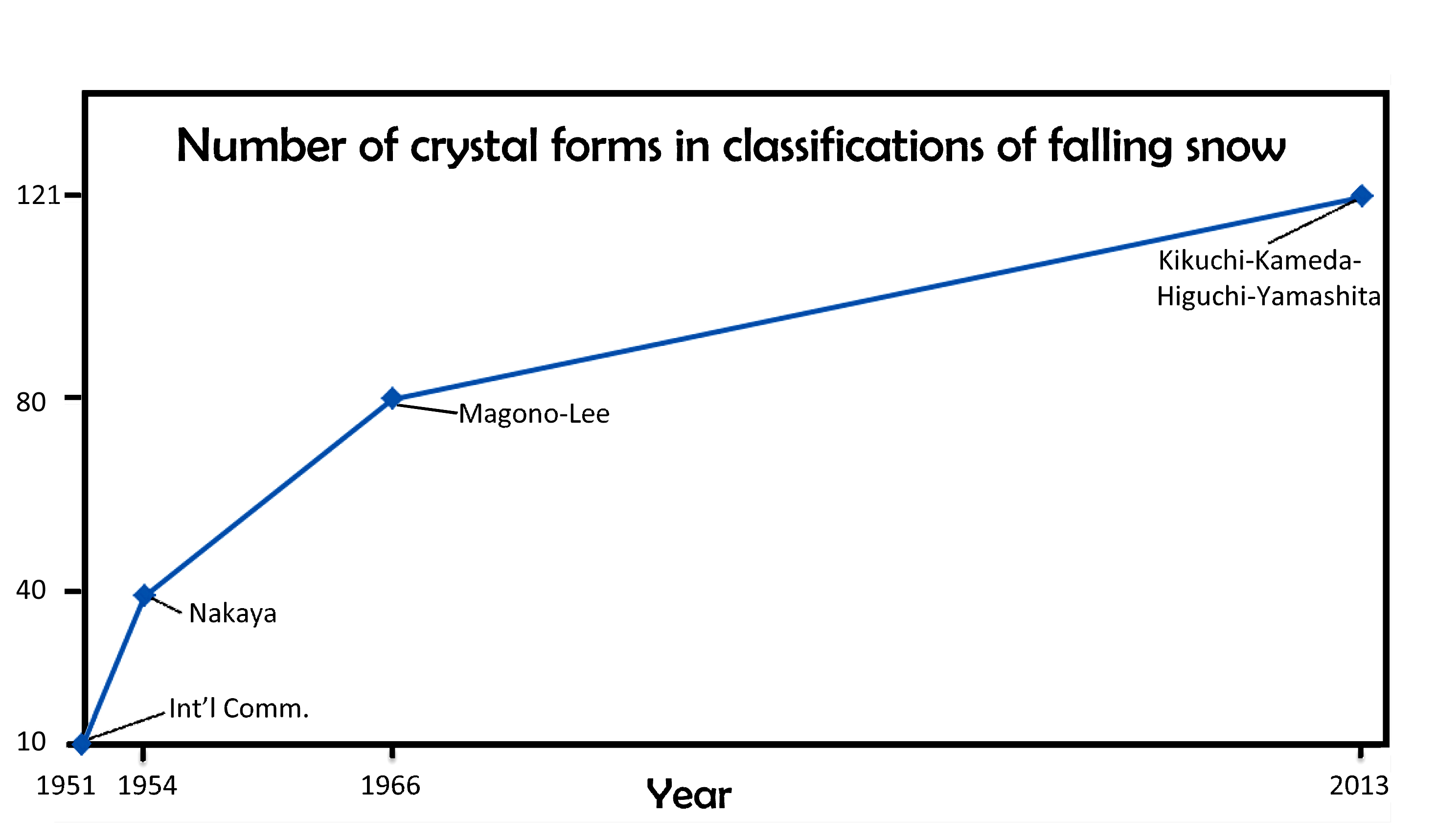

January 22nd, 2014When I last wrote about the classification of falling snow and ice (02/14/2010), I discussed the 1966 Magono-Lee system. At the time, this system was the most recent one, and as such, the one generally used in meteorology. And to those who wondered how many types of icy precipitation exist, Magono and Lee would tell you 80 types.

Although 80 sounds like a lot, Magono and Lee did not include at least one very common type as well as a few other interesting types. This major omission was snow-crystal aggregates, generally known as “snowflakes” by meteorologists. These are individual snow crystals that have stuck together during their fall and arrive as large open clusters of crystals, often with tens–to–hundreds of crystals in a big, round blob. (To meteorologists, a snow crystal is not a snowflake; rather, a snowflake consists of many snow crystals. It is like the difference between a trundled rock and a landslide.) In fact, the snowflake is probably the most common type of snow precipitation in most areas that receive snow. Several other omissions of the Magono-Lee that I mentioned in my 2010 posting included spearheads, seagulls, and the both the 18- and 24-branched forms.

If you were waiting for someone to fix the classification, well wait no more: we now have a new classification scheme that includes all of these and more. The new system has not one, but three types of snow-crystal aggregate (snowflakes), which are given the symbol “A” (for aggregate). There is also four types of spearhead crystal (symbol “CP8”), five types of seagull crystal (symbol “CP9”), and both the 18- and 24-branched crystals (P5e and P5f). In all, the new system has added 41 new types. In one big graphic, here is the new system:

The architects of this new classification scheme published the above table in summer 2013*. There were four authors (K. Kikuchi, T. Kameda, K. Higuchi, and A. Yamashita), making it harder to name the system after the originators, but hopefully their names will become known, just as Magono and Lee’s have.

I will discuss various aspects of this new system in subsequent postings. But for now, I point out that the number of basic types has increased over the years, from 10, to 40, to 80, and now 121. When will it ever end?

Of course, it may just keep increasing. In fact, if we plot the numbers vs the years, and look at the pattern, we might conclude “never”.

Rime falling from branches

January 24th, 2013While riding my bike home the other day, I saw what appeared to be a patch of light snow.

It was the only such patch around. Looking closer, I could see that it consisted not of snow, but of chunks of partly melted rime deposits. (Note how the pieces are long and narrow, like little icicles.)

Just above were the branches of a huge Douglas Fir tree. Perhaps there had been an over-active squirrel or two up there. Other trees still had their rime. Hard to see why only this tree would have its rime fallen off.

- JN

Crystal-to-crystal “communication” through vapor and heat

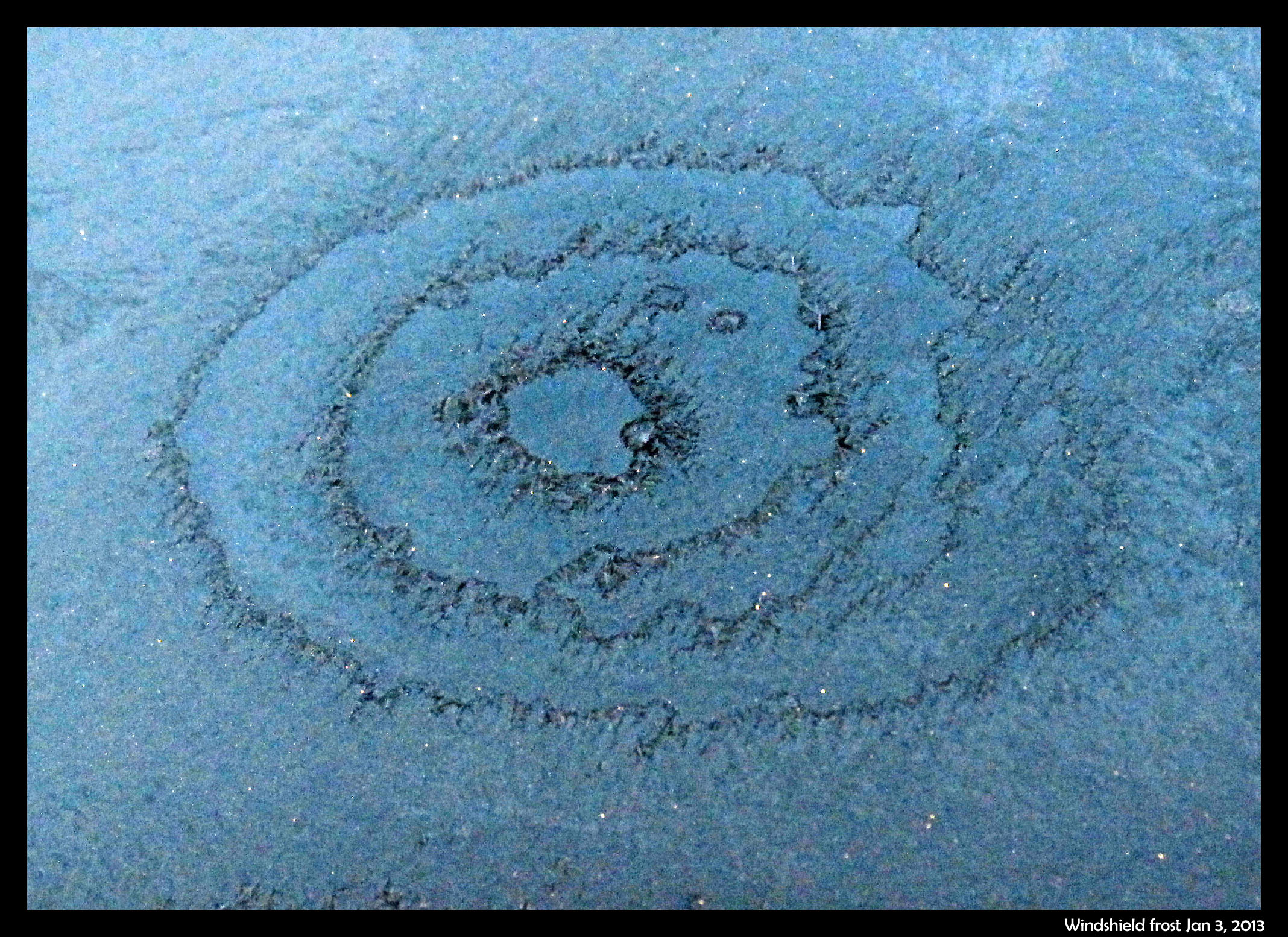

January 5th, 2013Two mornings ago, I saw this on the windshield of a parked car.

The bulls-eye pattern wasn’t centered on any particular feature on the windshield, and there were similar, though less developed, patterns nearby. See them on the photo below.

The dark parts are largely frost-free regions, and thus are regions that dried out during the crystallization event. (It was still dark when I took the shots.) Later, under a brighter sky, I saw a different pattern on the hood of another car, a pattern that I figure has a similar cause. In the hood case, shown below, the dry regions are bright due to reflection of the sky.

Now, about those concentric rings …

I puzzled over a larger such pattern in the Feb. 5, 2010 posting “Ripples”. The causative process that I proposed back then seems consistent with this newer observation, but I will clarify it here.

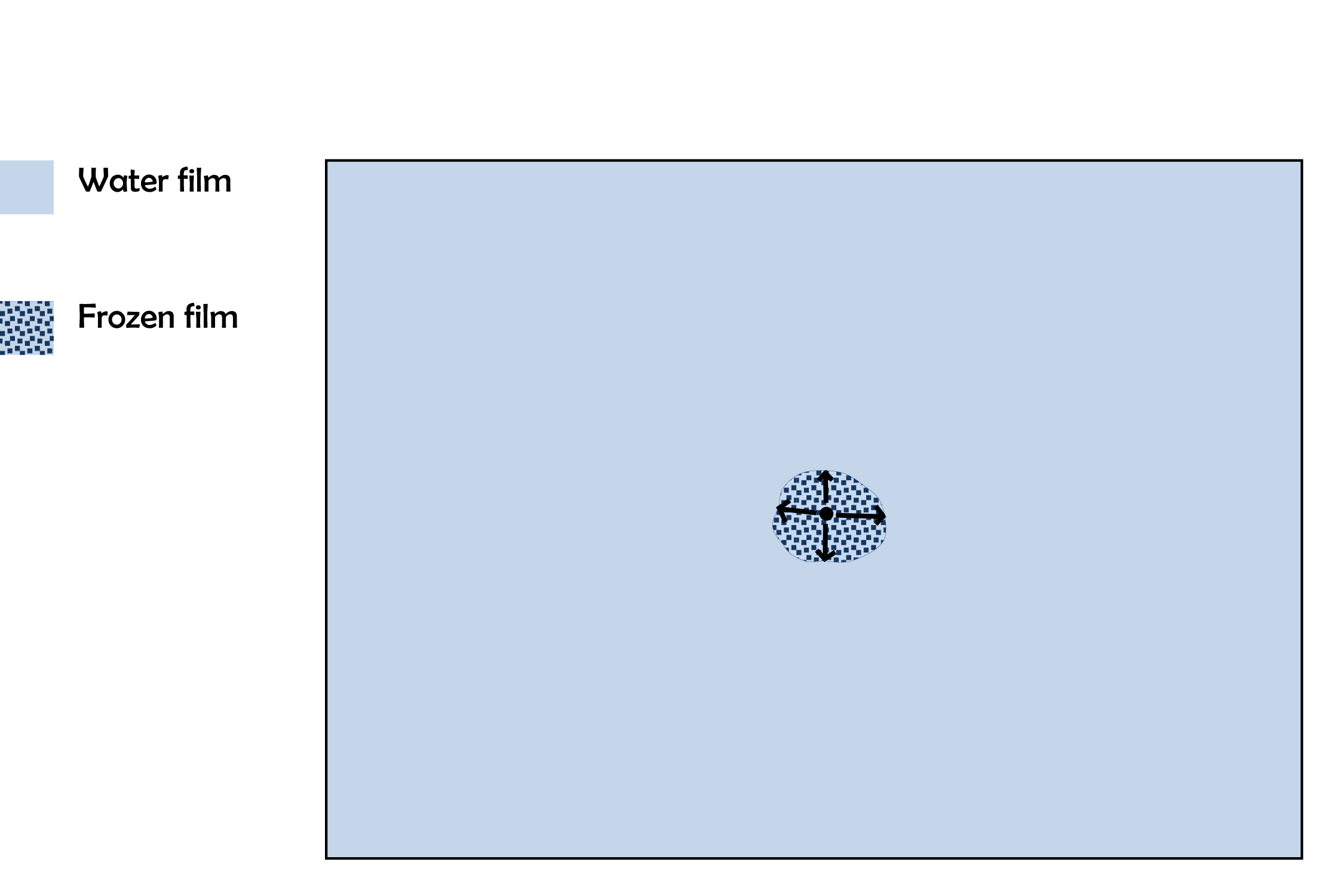

Before the first frost formed, the windshield, though seemingly dry, nevertheless had a thin layer of liquid water. This thin film had cooled to some temperature below freezing. (See the sketch “How hoar frost forms” in the Jan. 11, 2012 posting.) As the windshield and water film continued to cool, freezing was inevitable; the only issue was where. The first such spot to freeze must have had some feature, however minute, that was advantageous to freezing. It may have been a nucleant particle (e.g., a mineral dust grain, a type of bacteria, or even a tiny fleck of ice that wafted in from somewhere else), a slightly cooler spot, or a slightly thicker water film (e.g., from a scratch or indentation). But for whatever reason, the ice formed there first.

Now suppose the ice spreads outward from the nucleation spot in all directions with about the same rate. I suspect this happens when the film is extremely thin, as it would have been under the relatively dry conditions of this day. So, the frozen film grows outward, roughly as a disc. See the sketch below; the black dot in the center is the first place that froze.