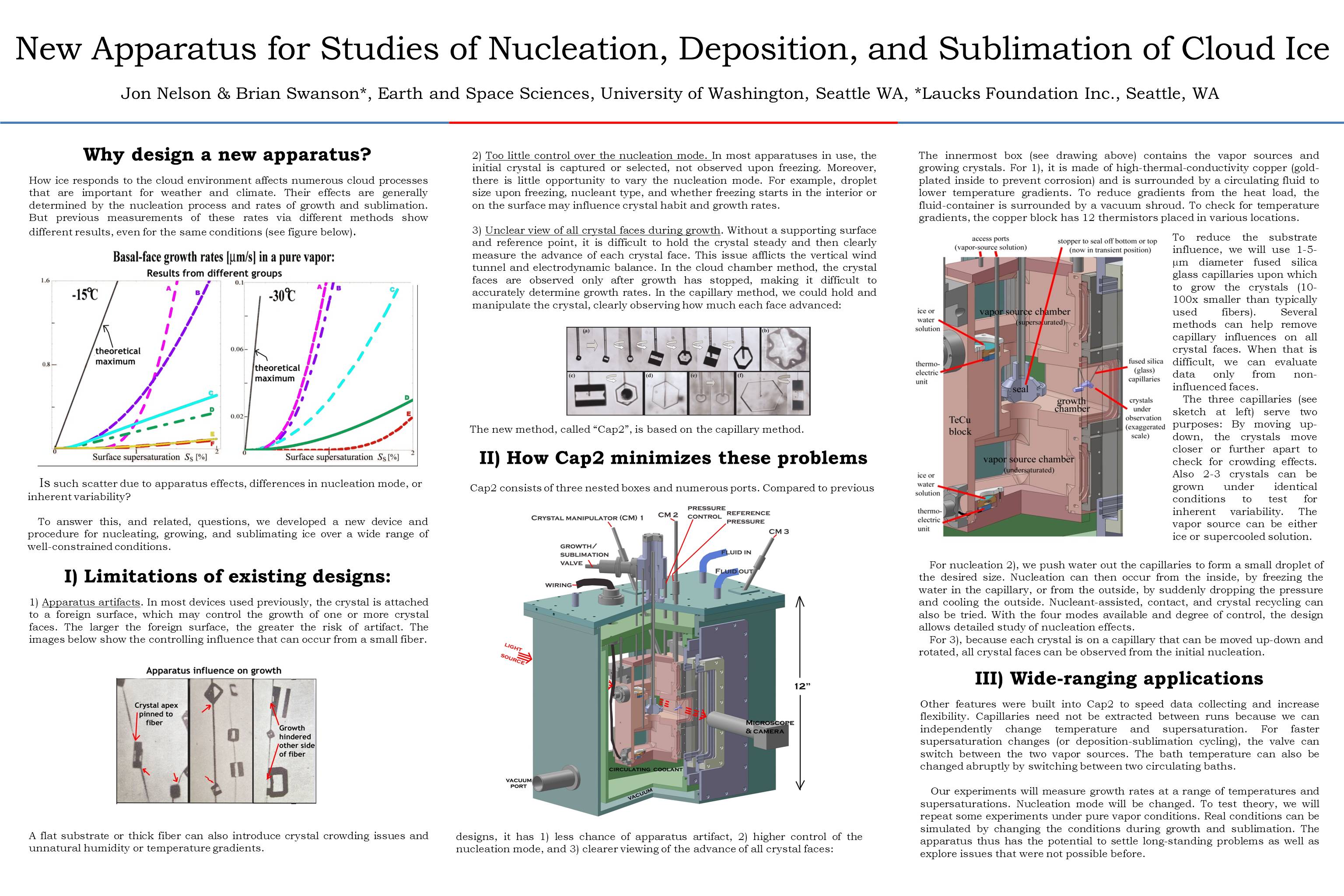

A Crystal Pair, Several Views, and a "Man on the Crystal"

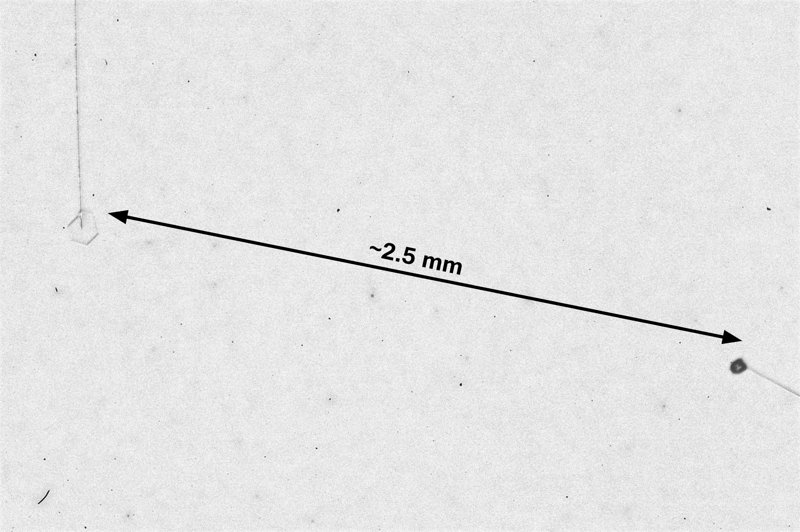

December 19th, 2014One advantage of the new apparatus is the capability to grow up to three crystals at a time, each on its own capillary. It is also very useful being able to move each capillary around. Having success with a single crystal, we tried it with two, and much thinner, capillaries.

This time, we had to cool the apparatus down to about -38.5 C before they appeared (previous cases were about -20 C), and to my surprise, they both appeared at about the same time. (Polycrystalline blobs, as are more common at these low temperatures.) Due to some troubles we were having with the vacuum (later discovered to be simply a case of the pump getting shut off), we warmed the crystals up to -17 C, sublimated them, and regrew them.

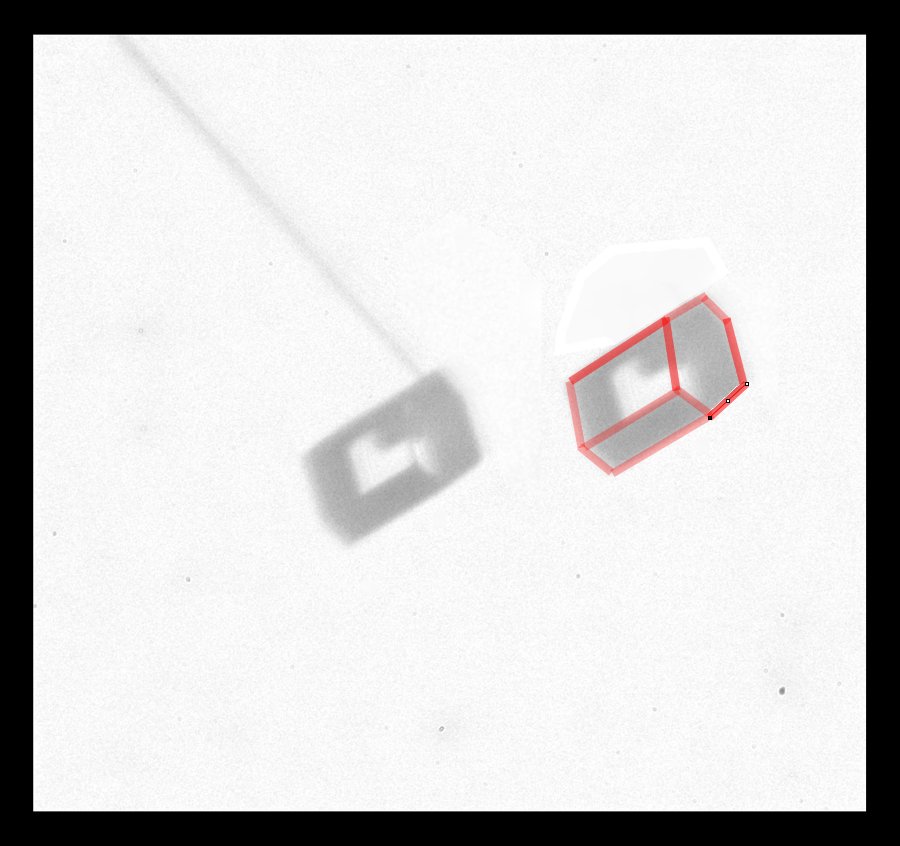

The capillaries slide up-down on axes that intersect, designed this way so we can bring the crystals nearer or further apart. For the above image, they were relatively close. The crystal on the left is a thin plate, whereas the one on the right appears to be a short column. Both grew under the same conditions, but grew into different forms.

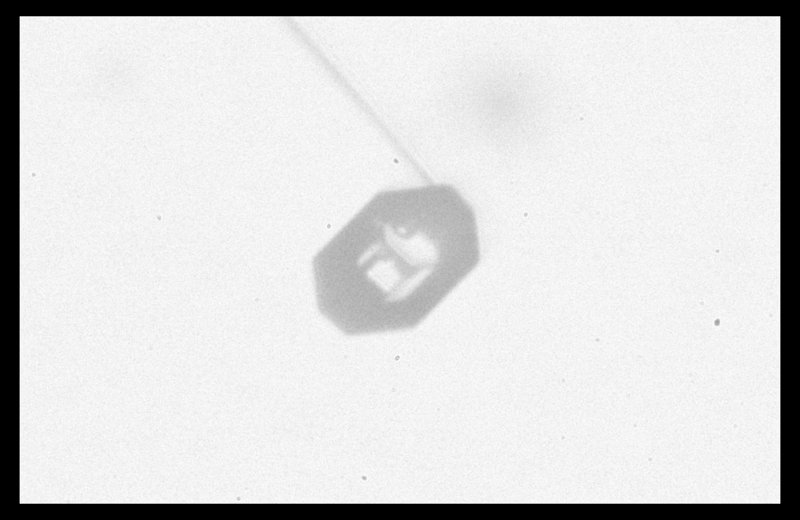

On closer look, the rightmost crystal revealed itself to be more interesting than initially thought:

The apparent "man in the crystal" (i.e., face, as in the "man on the moon") shown in the view above arises from dark lines, which are due to face-face edges on the other side of the crystal, a horizontal "terrace", also on the other side, plus an air pocket inside the crystal.

Also, the crystal appears to be eight-sided around the perimeter, but this is again an illusion due to perspective. Rotating the crystal around the main capillary axis instead suggests a four-sided form:

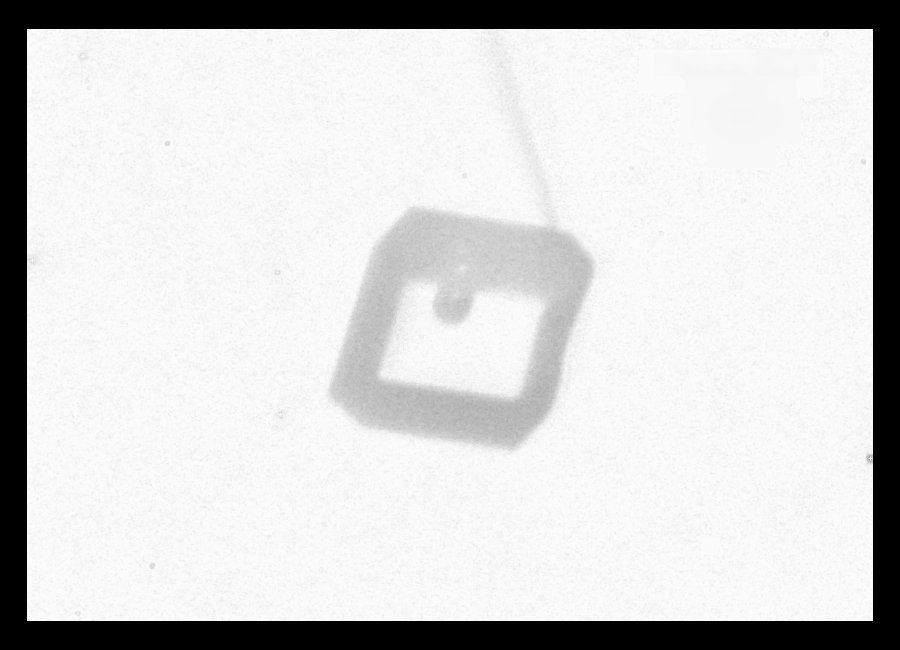

Whereas another rotation suggests a common hexagonal prism:

The horizonal extent of the crystal is about 150 micro-meters (microns). The view above clearly shows the interior air pocket. Also, on the right, you can see the profile of the "terrace" mentioned above.

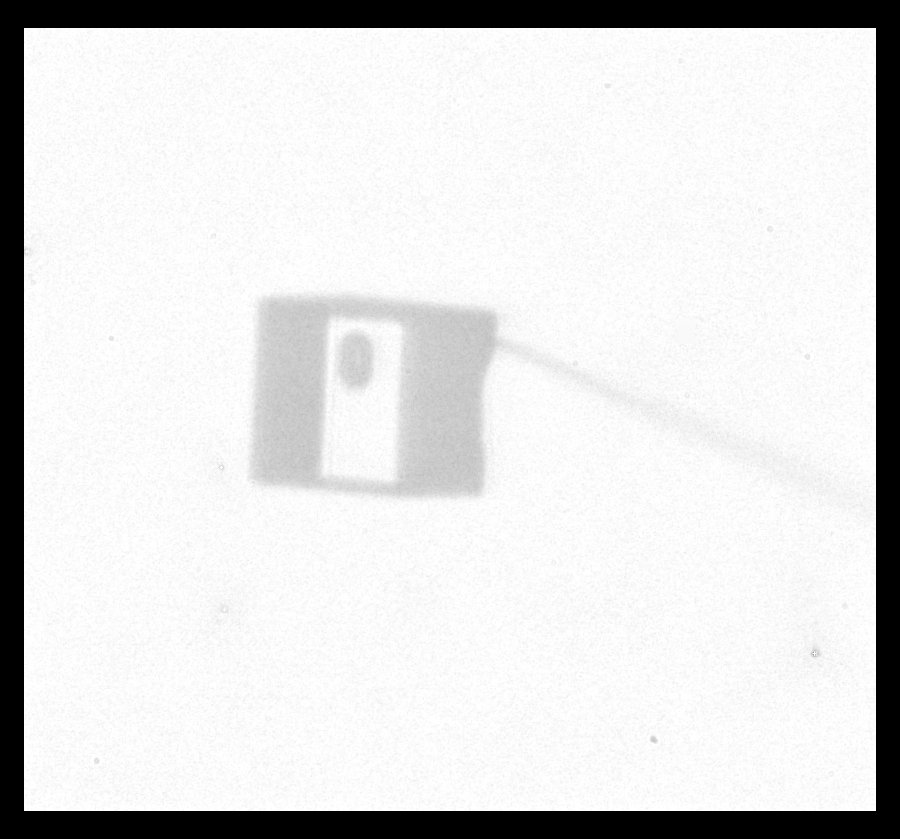

Another rotation, giving another view, helps to clear up the mystery of the 3-D crystal shape:

The crystal is a short hexagonal column, but two opposite prismatic faces are much larger than the other four (because they grew much slower). I copied the crystal image at right and outlined the crystal edges in red. This shape of crystal is thought to give rise to one of the "Parry arcs" in the sky, which I showed in an earlier post.

Another interesting thing about this crystal is its very weak attachment to the capillary. The molecular forces holding it up were so weak that torques arising from the pull of gravity would cause the crystal to slowly rotate downward. In general though, these cases show how useful it is to be able to move and rotate the crystals.

--JN

New Capillary Crystal-Growth Device

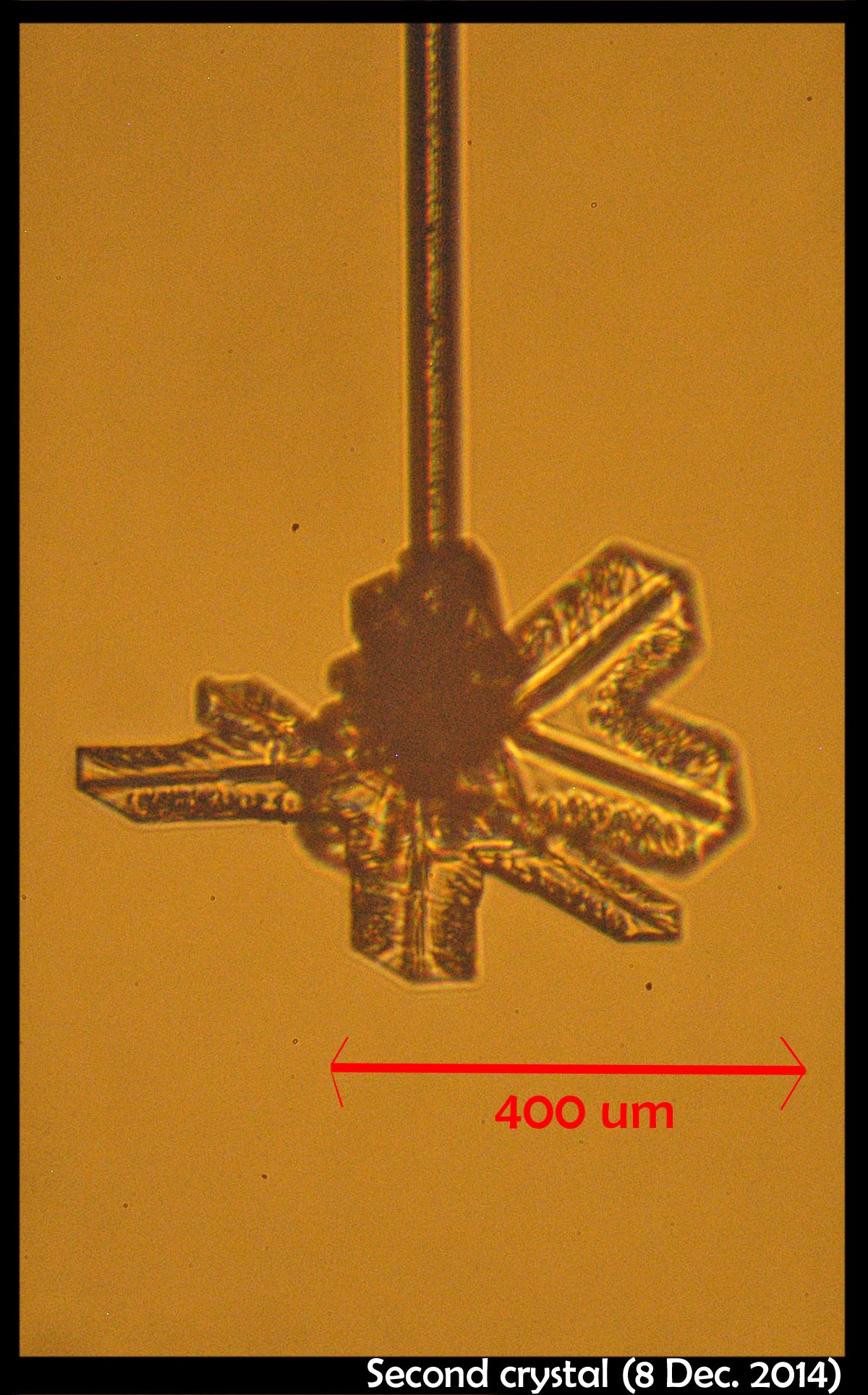

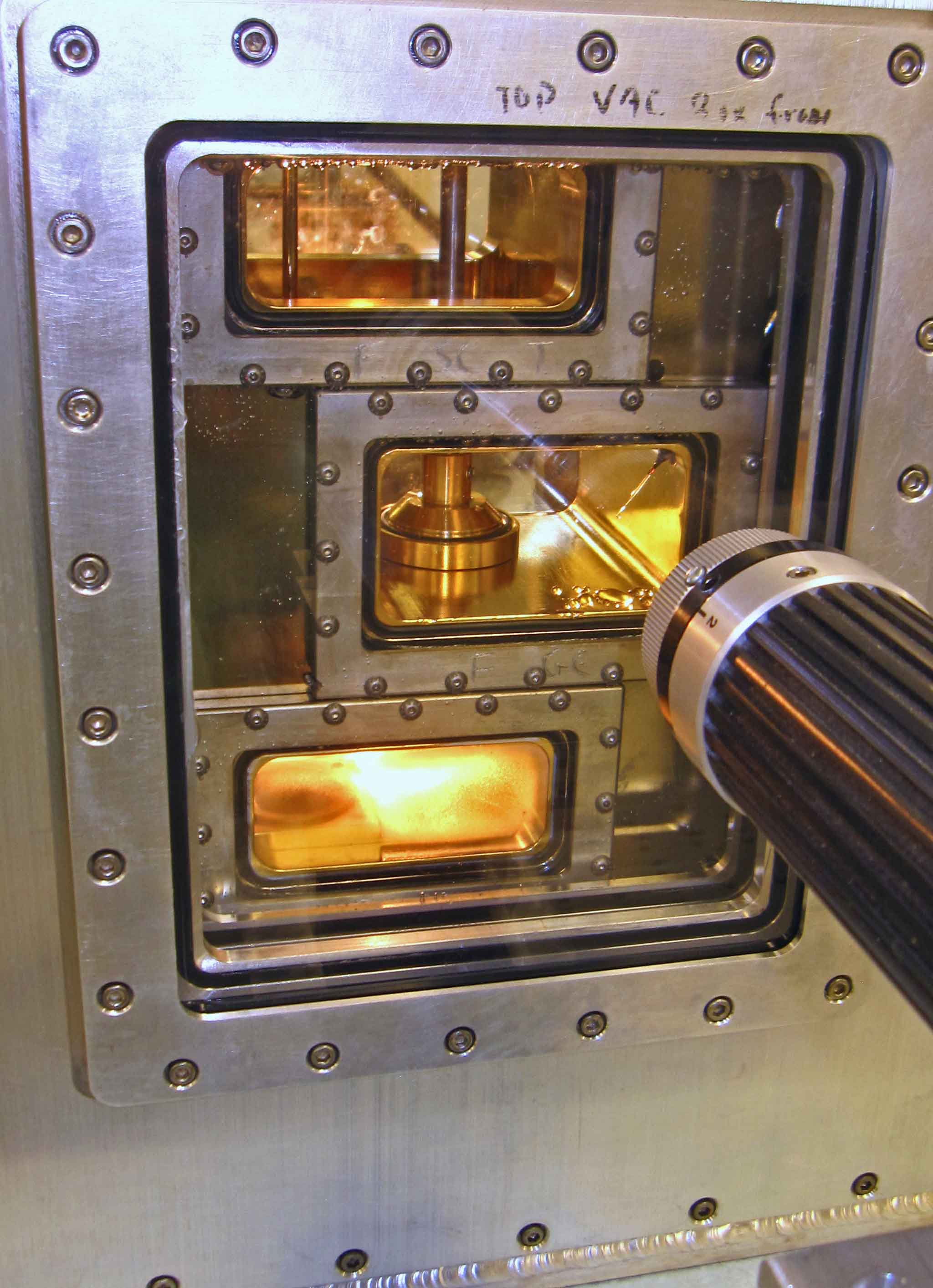

December 11th, 2014After several years of planning and several more years of construction, our new crystal-growth device is operational. We are now tuning the electronics, vacuum system, data collection method, and other aspects, but we can indeed produce ice crystals on a glass capillary under controlled conditions.

The thing works!

The first two capillaries we tried basically exploded, due to my having loaded them with way too much water, but the third produced a nice frozen droplet. The frozen droplet, or "droxtal" did not grow on account of all the water that had spewed down from the previous attempts, but we cleaned up the debris, and started anew. That case, pictured above, produced a nice spatial dendrite. I could control the growth condition quite well, and kept growing, sublimating, and regrowing the same crystal for a few days. We now need to refine our capillary-making method and make them about 10x thinner (as I used to do in my previous experiments).

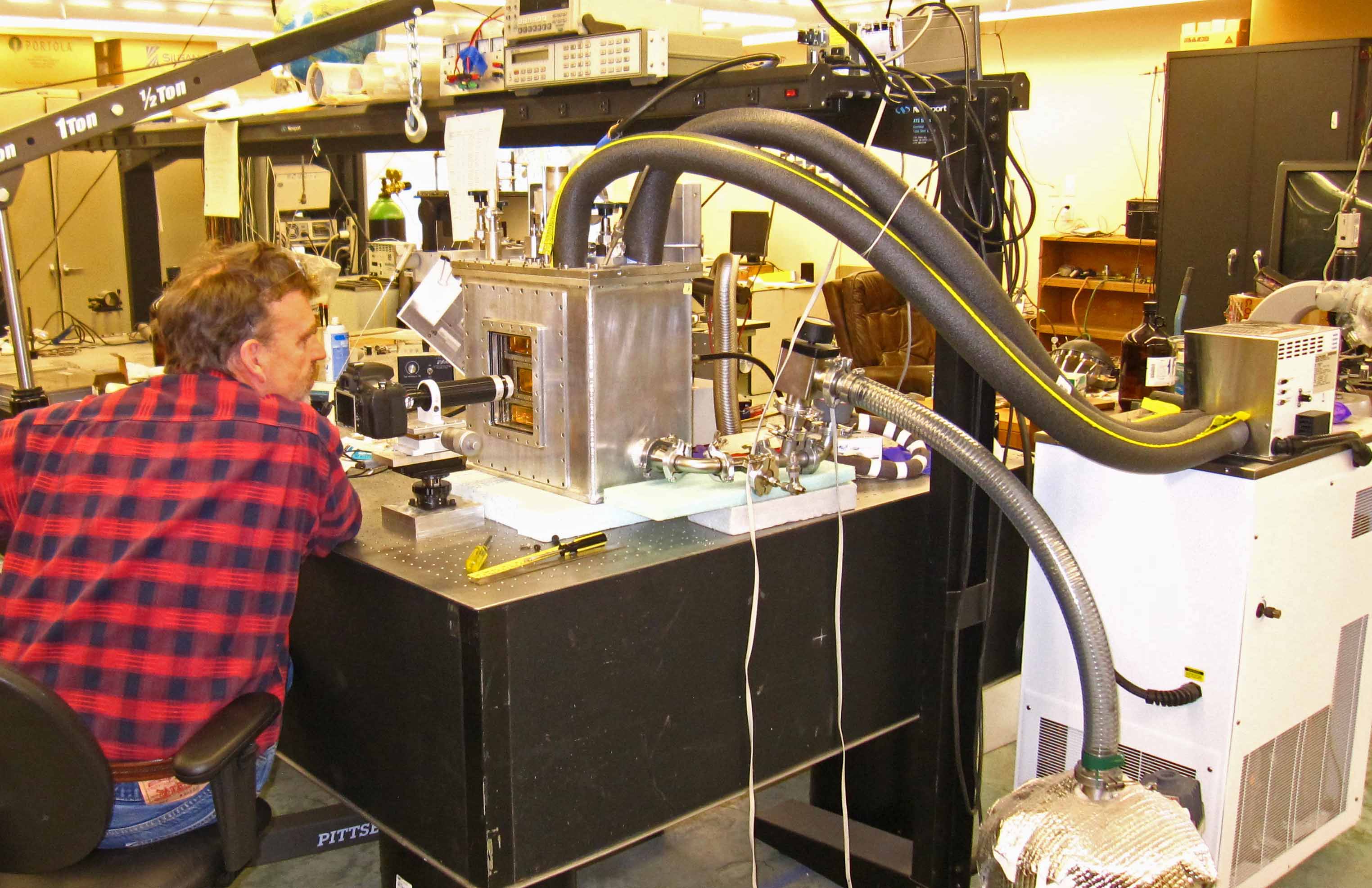

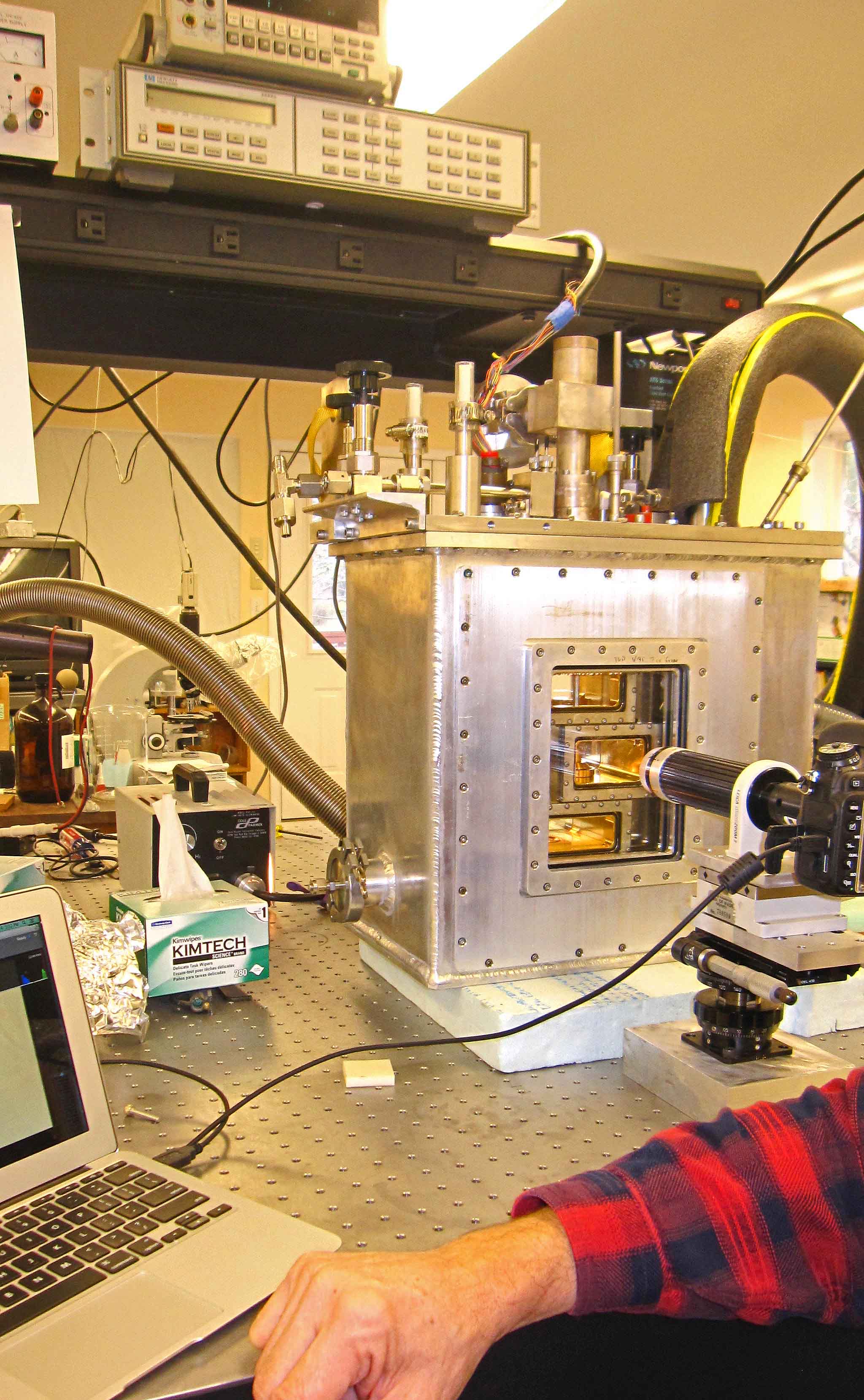

The overall setup is pictured below, Brian at the controls.

The white thing on the right is the cooler. It pumps cold methanol into the big aluminum box sitting on the table. That box is actually three boxes: an innermost crystal box (consisting of several chambers), a bath box that holds the cold methanol cooling fluid, and a vacuum box around that to help insulate the system.

All the controls enter from the top, so we have lots of things sticking up on top: fluid in-out ports, vacuum control of the growth chamber, reference chamber access, access to two vapor-supply chambers plus vacuum control of the chambers, a valve system to connect vapor to growth chambers, and a bunch of wires... The inside of the innermost crystal box is gold-plated to deter corrosion and help us keep contaminants to a minimum.

We hope to have more crystal images soon.

--JN

Freezing a Soap Film

December 1st, 2014Upon seeing this morning some recently posted pictures of freezing soap bubbles, I decided to give it a try.

Fortunately, we have been having freezing temperatures recently. And coincidentally, my older daughter had just purchased some glycerin for making hand lotion. (Glycerin is a very useful ingredient in soap-solution.) I mixed up a cup of solution, using crushed ice in the water to make it cold, found a bit of twine, and headed outside to a shady spot in back.

I soon gave up on blowing bubbles, and just tried freezing a film. It worked on the third try:

(As with all images on this blog, click to enlarge.)

Sometime later, I will work on freezing larger bubbles. I imagine though that if I had my polarizing sheets with me, even a frozen film could dazzle. Next time.

If you have experience freezing large bubbles, please let me know. My ice films would break within about a minute of the first signs of ice formation--it would be nice to know a better method.

- JN

Glaze-rime Ice Buildup Facing Creek

November 23rd, 2014Here's a reed of some sort, with a glaze of clear rime on the side facing a creek. How did the clear ice get there, and what is the white ice on top of it?

The fact that the clear ice is just on the side facing the creek indicates that the ice came from droplets blown off the creek. To have the ice buildup just on the side means that the droplets must have frozen soon after landing, but slow enough to spread out and fill gaps.

So, the droplet must have been larger than typical cloud droplets, and the temperature must have been within a few degrees of freezing. Clearly, the flowing water must have been above freezing, so the droplets must have cooled to below zero while drifting through the air.

A closer shot shows that the outermost ice, the white ice, is hoarfrost. Only hoarfrost would show the flat crystalline facets. Definitive proof that that ice grew out of the vapor that was blowing by. You can also see some hoar on the other side of the reed.

--JN

A Change in Habit

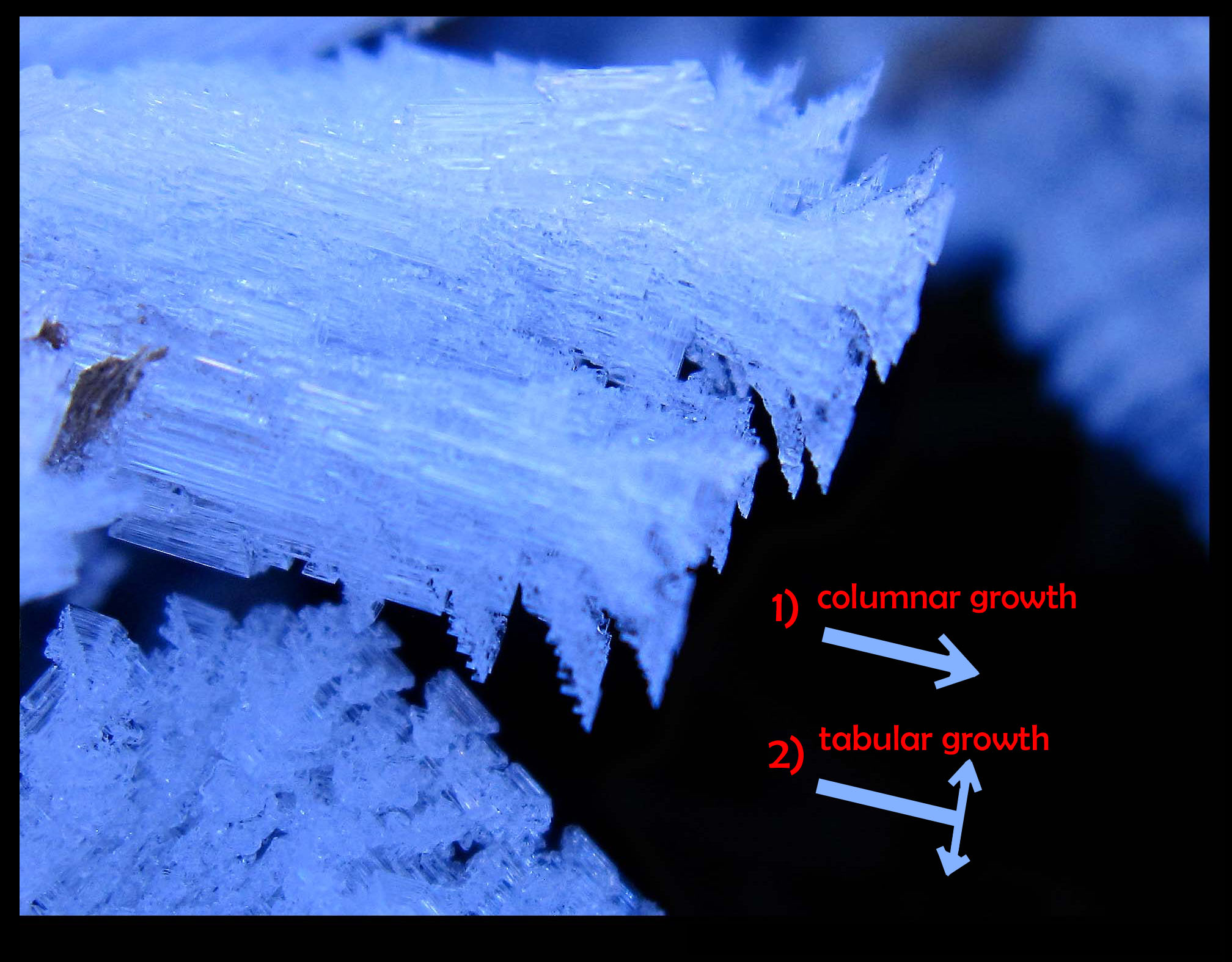

November 23rd, 2014The two main growth modes of snow and hoar (i.e., ice growth from the vapor) are columnar and tabular. In columnar, the shape is long and thin, like a pencil or cluster of pencils (bound snugly with a rubber band). In tabular, the shape is plate-like or fan-like. When a crystal form has an easily expressed shape, like a column or plate, we say it has a certain habit.

In hoar frost that had been growing for several nights, I saw some that had changed their habit.

On the first night, when the vapor was more plentiful, large columnar forms appeared. This habit grows between -3 and -8 C. On a subsequent night, the temperature got colder, below -8 C, leading to tabular growth. More vapor exists out near the ends, so this is where we see the tabular habit.

The arrows above show the fast growth directions. There is a transition that sometimes happens when both of the main growth directions are fast, making a flare, or trumpet-horn shape (other times, it may be more of a cup or vase). Such a transition is far more common in hoar than in snow, because, I believe, hoar on the ground can experience a much higher excess of vapor.

The dark region in the background is the water of a creek.

--JN

Smaller Hoar Growing on Larger Hoar

November 22nd, 2014Cold air came down the interior, spilling through gaps in the Cascades, cooling the western side. In the Seattle area, we got our first frost on Nov. 11, but the days stayed cold. Areas in the shade never lost their hoar, so the hoar frost kept growing.

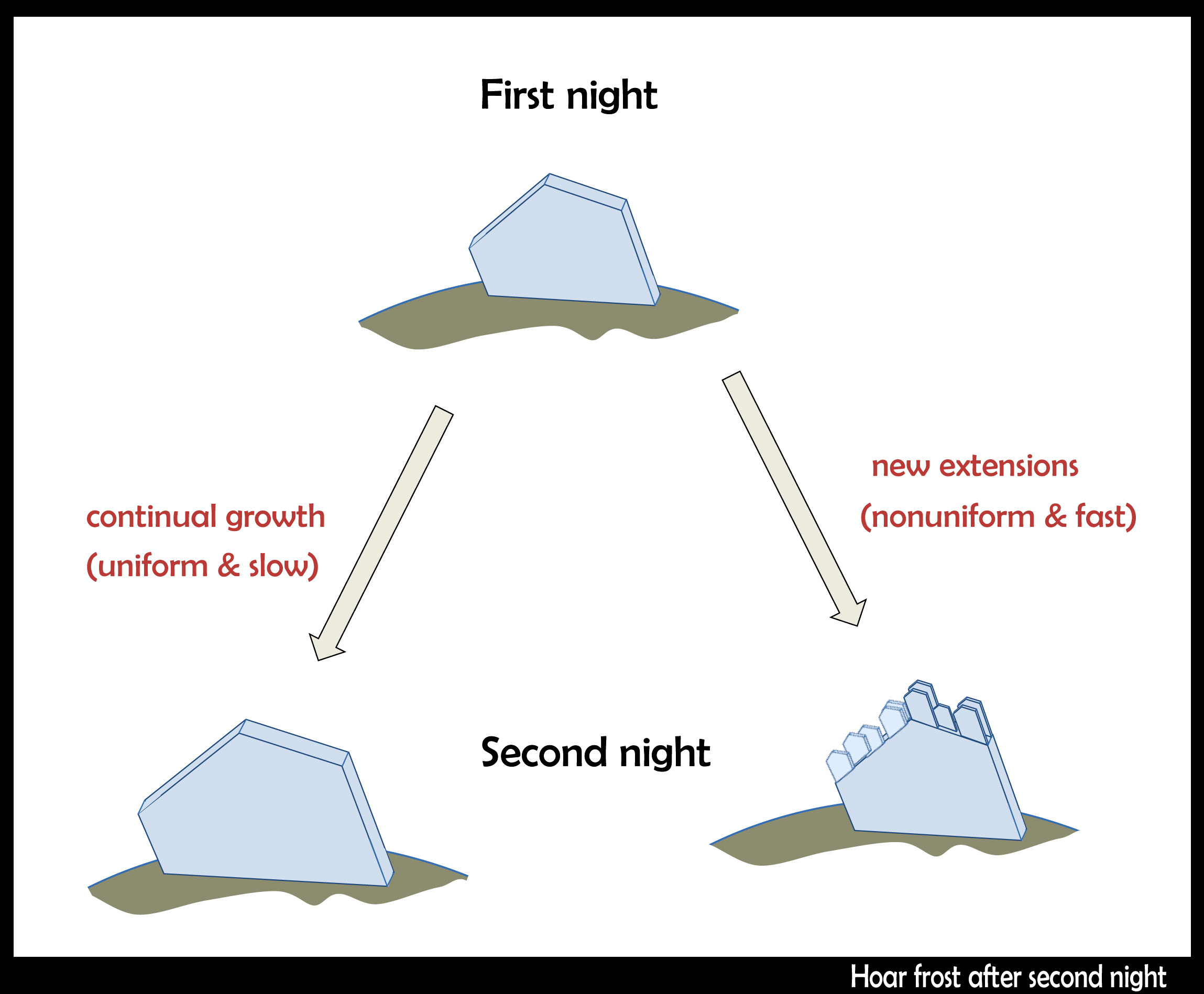

But does a hoar-frost crystal continue growing the same way as on the previous night? Does it keep extending uniformly, getting larger and larger, keeping the same general shape?

Or do smaller hoar crystals form on previously grown larger crystals?

A few days later, I found myself walking in Maple Falls near Mt. Baker. In a shady pocket near my feet, I saw some hoar. Subtly different -- it appeared like small, translucent leaves encrusted on their edges with hoarfrost. But it turned out that the "small leaves" were actually tabular hoar (plate-shaped). That is, hoar encrusted on hoar: smaller crystals on larger crystals.

When frost resumes growing on previously grown frost, the other possibility may also happen; that is, the hoar just resumes growing the way it did the previous night. But I think this is generally quite rare because it would require very slow and constant growth conditions, which is generally incompatible with the diurnal temperature cycle. See the sketch below for both possibilities.

Note that I write above 'smaller hoar crystals grow on the larger ones' even though technically, they are all the same crystal. You can see this is true by the fact that their faces all line up.

The view that got me to look closer:

- JN

New habit diagram for branched tabular crystals

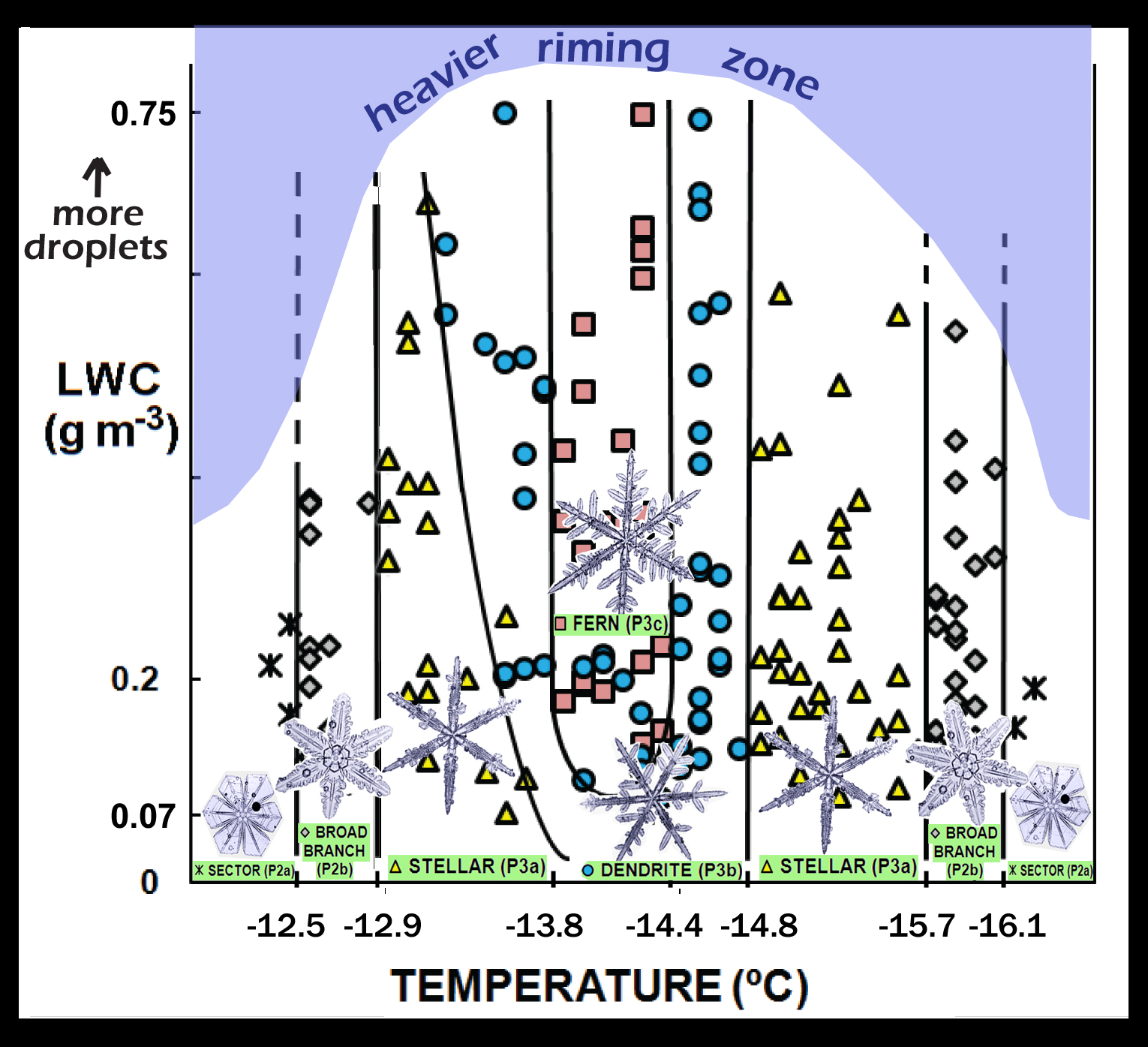

August 24th, 2014You might call these “snowflakes”. But let's be specific here with the names.

Anyway, a close associate who has been sweating over his snow-crystal growth machine in Japan for many years has just published his latest results. His machine is a vertical supercooled-cloud wind tunnel, which is like a thin column of cloud in which one can observe a single floating crystal. The crystal is in a climate-controlled box containing a droplet-infused stream of uprising air.

For this study, he focused on the crystal habit (i.e., shape) in the temperature range that we tend to get the large six-pointed stars. In addition to varying the temperature, he varied the density of droplets in the air. Nobody had done this before, certainly not as carefully and complete as he. Though he found lots of interesting results, I'll focus here on the following diagram:

Given its similar layout to the well-known Nakaya habit diagram, let's call this the Takahashi habit diagram. Whereas Ukichiro Nakaya showed us the crystal shape as he varied the temperature and humidity, Prof. Tsuneya Takahashi varied the temperature and droplet density (“LWC” on the vertical axis stands for liquid water content).

The basic findings: As the temperature decreases from left to right in the diagram, the crystal form goes from the very wide-branched sector crystal (see the “sectors”?) to the longer branches of the broad-branch crystal, to the even longer and narrower branches of the stellar crystal, to the crystal with sidebranches on each branch, called a “dendrite”, and then the pattern reverses back to sectors.

In the middle of this temperature range, something else happens. If he increased the density of cloud droplets in the dendrite regime, he got the more finely sidebranched fern forms. Ferns differ from dendrites only in the number of sidebranches they have. Fern crystals look more like fern plants because they have more offshoots. But at other temperatures, adding more droplets did not change the crystal form. In fact, the crystal size did not increase with more droplets, although the mass did increase.

If you observe some crystal that looks similar to one on the Takahashi diagram, you may infer that it grew under the indicated conditions. But this is not yet the final story: for instance, the amount of sidebranching is also thought to depend upon the temperature and humidity fluctuations. More fun ahead!

- JN

It’s not a rainbow (it’s better)

August 12th, 2014In summer, the sun reaches higher elevations, bringing the possibility of new atmospheric displays. I saw this one in mid-June.

The top, upward arc is the more familiar and common 22-degree halo. But pay attention to the one on the bottom. Its colors look like a rainbow, but it has nothing to do with water drops of any sort.

It is the circumhorizontal arc, and it is as rare as it is beautiful. The colors are, in fact, more pure than those of the rainbow, and its origin is far more remarkable. It is remarkable because of the surprising set of conditions that must hold for it to exist. First of all, the particular region of cloud (at a certain angle to our eye) must consist mostly of ice crystals. Second, the crystals there must be nearly perfect tabular prisms. And third, these crystals must be in sufficiently non-turbulent air and of such a size that they fall in a nearly exact horizontal position:

The new ice-crystal-growth apparatus

July 1st, 2014After a few years in the making, our new device for growing single ice crystals in a well-controlled laboratory environment is nearly ready. We are just adding a few small accessory pieces to allow us to start testing. I was to describe the apparatus at the cloud-physics conference this month in Boston, and made a poster to present, but decided to opt out. But, having spent a few days making the poster, I present it below.

As with all images here, click on image to see large-scale view.

And below is the same, but in blog format.

Halo in the sky? Uh, I don't see no halo...

April 20th, 2014After a few days of fine bright spring weather, the barometer falls and a south wind begins to blow. High clouds, fragile and feathery, rise out of the west, the sky gradually becomes milky white, made opalescent by veils of cirro-stratus. The sun seems to shine through ground glass, its outline no longer sharp, but merging into its surroundings. There is a peculiar, uncertain light over the landscape; I 'feel' that there must be a halo round the sun!

And as a rule, I am right.

The quote, from Minneart* describes a common ice-related atmospheric apparition. It appears in skies all over the world far more often than the rainbow, yet few notice it. As a graduate student, I read about halos and often looked for one, but didn't notice it myself until someone else pointed it out. As a post-doc in Boulder, I was out walking with Charles Knight, and I mentioned my lack of success. He glanced up near the sun, pointed, and said “why there's one right now”.

What I had missed in my readings had been the fact that most halos are rather indistinct and often incomplete circles. Indeed, now when I point out the most common one (the 22-degree halo) to someone nearby, they often don't see it. But occasionally, it is sharp enough (and colored) to the extent that anyone will see it if they bother to look up and glance toward the sun. And often it occurs with other ice-crystal apparitions that are even more obvious.

Last fall, while perched high on a rock face, belaying my partner up**, I saw such a vivid display.

The bright spot is called a “sun dog”, “mock sun”, or “parhelia”. They, one on either side of the sun, usually appear together with the 22 degree halo. Indeed, the sun dogs very nearly mark the spots where that halo intersects another arc called the parahelic circle. Their cause: horizontally oriented, tabular ice crystals.